First web exhibit and essay February 10, 2013

Wonderful Creatures in Clay

a photo/essay in appreciation of animals in American Art Pottery

a photo/essay in appreciation of animals in American Art Pottery

Serpent bowl by Frederick Hurten Rhead

University City, Missouri 1911

8" x 3" Signed by the artist

Recently a group of four tiles by Rhead from University City which together comprise an image of a peacock set a new record for American Art Pottery previously held by another work of Rhead's, an 11 1/2" landscape vase done in Santa Barbara. The collectors to whom I had sold that landscape vase, had lived with it for a decade or more and then sold it through David Rago's Craftsman auctions in New Jersey for $516,000 in March of 2007. I had bought it years before, sold it once, bought it back a second time a few years later and sold it once again. The four tile peacock panel, just shy of 21" square, exceeded that sale. It also sold through Rago's Craftsman Auctions in October of 2012 and realized $637,500. In June of 2012, Craftsman auctions also sold a 6 1/2 inch mushroom vase for $150,000. Examples like these are clearly all incredibly valuable and impossibly rare... for images, see Google and my archives.

Frederick Hurten Rhead University City serpent bowl. 1911

(See the current March 2013 of Antiques Roadshow Insider magazine for further information.)

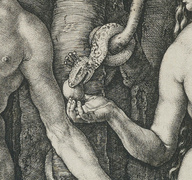

The use of the serpent as subject matter for American Art Pottery is more uncommon than one might expect. While the snake figure is prominent in Native American pottery, there are very few examples of snakes in later American Art Pottery: most notably they are found on Southern jug ware and on the brothers Kirkpatrick's Anna pottery in regard to the issue of temperance as well as on pieces by the Mississippi potter, George Ohr. This low bowl must certainly be a singular instance of the serpent in Frederick Rhead's design vocabulary. The serpent bowl is a strong example of the highly carved designs from Rhead's consummate University City period's production. It was here in 1909 in St. Louis, Missouri that Taxile Doat, Adelaide Alsop Robineau, W. V. Bragdon, and Frederick Rhead, four premier ceramicists of the early twentieth century, first joined the faculty of the People's University, a branch of the American Women's League, for a few brief years to teach, write, and, in the process, cross influence one another's work.

Rhead's subtle mastery of the medium is not always immediately apparent when viewing his work. But, as one of America's greatest potters, his intention is always present, if hidden at first within his designs. When we look at his peacock tiles from this period or the large forest mushroom vase, the image is directly across from us, imposing itself upon us, eye to eye. As an artist, Rhead may confront us full on with the peacock's myriad "eyes of beauty" or make us focus in on the mushrooms' rising dance within the woods. Those decisions are inherent in the form the individual designs take across the surface of the vase. In this instance, Rhead has chosen the form of a low bowl to house the image of the snake in nature. Here the form itself forces us to look down upon it in order to see the reptile in its environment. The bull rushes, the clouds and its circular presence are all interwoven in that downward view. How quietly his artistry directs our response, conjuring up the ancient relationship between man and this emblematic creature in the process, especially in a viewer influenced by Judeo-Christian culture. Position. Our relationship to the animal and its relationship to us is made manifest in this way and is underscored at the same time. We can't help but feel it under our skin. We are in this powerful creature's domain...

During his time at University City, Rhead employed the use of deep engraviture across his vessels' surfaces. It is used to great effect in this example. The many scales of the dark blue snake and its cream-colored underside are intricately inscribed, twining and turning around the circle of the bowl, bringing the animal to life. As it moves through the grass and ochre background clouds, nature is somehow subordinate to it . The articulation his stylus brings to the snake's body and the angular geometries of its head give it depth and the implication of life in motion. It is larger than everything else depicted, almost covering the pictorial band in its entirety. It is the serpentine world we see and feel, the heat of the day reflected in the sunny clouds, the earth on which it travels felt in the closeness of its body in the green blades through which it weaves timelessly.

I once heard the noted scholar, Eugene Hecht, speak about Van Briggle pottery at the Arts and Crafts conference one year at Grove Park in North Carolina. He showed an image of Van Briggle's Despondency vase on the large screen behind him as he spoke about the young Artus Van Briggle's artistry and health. Here was a young man who had been one of the top decorators at the Rookwood pottery in Ohio, arguably the largest and most important firm producing ceramic art ware of the day. He had been sent to Paris to study the creations of Europe's best potters. Coming back from his sojourn and experiments in clay there, in 1899 he moved with his young wife, Anna, to Colorado for his health. He was all but forced to if he wanted to live. Suffering from tuberculosis, he needed the drier climate that life in the West offered him. One imagines his thoughts filled with many new designs for his equally new venture in clay there. Soon his pottery was producing some of the most nouveau examples of American pottery, sinuous plant forms fused with his vase's shapes. All twenty-four of his pieces were accepted and won gold, silver and bronze medals at the Paris Salon of 1903. Similarly, his work was awarded gold and silver medals at the Louisiana Purchase Centennial Exposition of 1904. Despite his fight to survive his illness, Artus van Briggle passed away while the exposition was still ongoing. The cases holding his pottery were draped in black. Hecht asked the audience to look once again at the slide of one of Van Briggle's most personal creations, this vase he called Despondency, and then began to describe it to us: here was a large vessel surmounted by a naked male figure, curled up in the fetal position, on his side at the edge of the vase's mouth looking downward into the abyss, the dark core of the vase upon which he languished for that unique moment in time... After that talk and that description, I knew I would never look at the Despondency vase in the same way again.

It is said that Frederick Rhead spent ten thousand or more hours conducting some sixteen thousand experiments in order to develop his mirror black glaze. While it has been widely held that he did not discover the formula until he moved to Santa Barbara sometime between 1913 and 1917, in truth he finally achieved the long sought-after mirror black earlier than that, at the Arequipa pottery in Fairfax, California a year or two after he had left University City. I have a number of examples which substantiate this assertion. If he had discovered the formula for a mirror black glaze even earlier when he was in Missouri, it was a conscious decision on his part not to use it in regard to the upper and lower fields which surround the broadly banded landscape of the University City serpent bowl. The color is a matte black which has undulations of glaze dripping down over the bowl's body. It is not the reflective black of his later success; rather it is a mysterious and impenetrable one which confounds and stops us from entering at the same time, like the inky fluid an octopus ejects when threatened, creating a filmy screen behind which it hides and then escapes from the scene. Notably, the serpent's head extends across the edge of the landscape's band into this blackness which leads to the mouth of the bowl; his long tail also enters into the dark field below the landscape and wraps itself firmly around infinity's dark side. Rhead is telling us something; his design is speaking for him: The snake's powers exceed the daylight in which it is seen by the viewer. It is a celestial or moral voyager, equally at home in the sunlight and in the surrounding darkness above and under it. Perhaps even more so in the darkness, as there are no clouds or grasses there-only the snake itself and the broad expanse of black. Rhead's artistry enforces the symbolism of the animal which predominates over everything else depicted on the bowl. Some American Art Pottery rises to the level of mythic representation as other great art does. In this instance, Rhead's adder in the bull rushes, like Van Briggle's despondency vase, is just such an example.

SOLD

Isak Lindenauer

Frederick Hurten Rhead University City serpent bowl. 1911

(See the current March 2013 of Antiques Roadshow Insider magazine for further information.)

The use of the serpent as subject matter for American Art Pottery is more uncommon than one might expect. While the snake figure is prominent in Native American pottery, there are very few examples of snakes in later American Art Pottery: most notably they are found on Southern jug ware and on the brothers Kirkpatrick's Anna pottery in regard to the issue of temperance as well as on pieces by the Mississippi potter, George Ohr. This low bowl must certainly be a singular instance of the serpent in Frederick Rhead's design vocabulary. The serpent bowl is a strong example of the highly carved designs from Rhead's consummate University City period's production. It was here in 1909 in St. Louis, Missouri that Taxile Doat, Adelaide Alsop Robineau, W. V. Bragdon, and Frederick Rhead, four premier ceramicists of the early twentieth century, first joined the faculty of the People's University, a branch of the American Women's League, for a few brief years to teach, write, and, in the process, cross influence one another's work.

Rhead's subtle mastery of the medium is not always immediately apparent when viewing his work. But, as one of America's greatest potters, his intention is always present, if hidden at first within his designs. When we look at his peacock tiles from this period or the large forest mushroom vase, the image is directly across from us, imposing itself upon us, eye to eye. As an artist, Rhead may confront us full on with the peacock's myriad "eyes of beauty" or make us focus in on the mushrooms' rising dance within the woods. Those decisions are inherent in the form the individual designs take across the surface of the vase. In this instance, Rhead has chosen the form of a low bowl to house the image of the snake in nature. Here the form itself forces us to look down upon it in order to see the reptile in its environment. The bull rushes, the clouds and its circular presence are all interwoven in that downward view. How quietly his artistry directs our response, conjuring up the ancient relationship between man and this emblematic creature in the process, especially in a viewer influenced by Judeo-Christian culture. Position. Our relationship to the animal and its relationship to us is made manifest in this way and is underscored at the same time. We can't help but feel it under our skin. We are in this powerful creature's domain...

During his time at University City, Rhead employed the use of deep engraviture across his vessels' surfaces. It is used to great effect in this example. The many scales of the dark blue snake and its cream-colored underside are intricately inscribed, twining and turning around the circle of the bowl, bringing the animal to life. As it moves through the grass and ochre background clouds, nature is somehow subordinate to it . The articulation his stylus brings to the snake's body and the angular geometries of its head give it depth and the implication of life in motion. It is larger than everything else depicted, almost covering the pictorial band in its entirety. It is the serpentine world we see and feel, the heat of the day reflected in the sunny clouds, the earth on which it travels felt in the closeness of its body in the green blades through which it weaves timelessly.

I once heard the noted scholar, Eugene Hecht, speak about Van Briggle pottery at the Arts and Crafts conference one year at Grove Park in North Carolina. He showed an image of Van Briggle's Despondency vase on the large screen behind him as he spoke about the young Artus Van Briggle's artistry and health. Here was a young man who had been one of the top decorators at the Rookwood pottery in Ohio, arguably the largest and most important firm producing ceramic art ware of the day. He had been sent to Paris to study the creations of Europe's best potters. Coming back from his sojourn and experiments in clay there, in 1899 he moved with his young wife, Anna, to Colorado for his health. He was all but forced to if he wanted to live. Suffering from tuberculosis, he needed the drier climate that life in the West offered him. One imagines his thoughts filled with many new designs for his equally new venture in clay there. Soon his pottery was producing some of the most nouveau examples of American pottery, sinuous plant forms fused with his vase's shapes. All twenty-four of his pieces were accepted and won gold, silver and bronze medals at the Paris Salon of 1903. Similarly, his work was awarded gold and silver medals at the Louisiana Purchase Centennial Exposition of 1904. Despite his fight to survive his illness, Artus van Briggle passed away while the exposition was still ongoing. The cases holding his pottery were draped in black. Hecht asked the audience to look once again at the slide of one of Van Briggle's most personal creations, this vase he called Despondency, and then began to describe it to us: here was a large vessel surmounted by a naked male figure, curled up in the fetal position, on his side at the edge of the vase's mouth looking downward into the abyss, the dark core of the vase upon which he languished for that unique moment in time... After that talk and that description, I knew I would never look at the Despondency vase in the same way again.

It is said that Frederick Rhead spent ten thousand or more hours conducting some sixteen thousand experiments in order to develop his mirror black glaze. While it has been widely held that he did not discover the formula until he moved to Santa Barbara sometime between 1913 and 1917, in truth he finally achieved the long sought-after mirror black earlier than that, at the Arequipa pottery in Fairfax, California a year or two after he had left University City. I have a number of examples which substantiate this assertion. If he had discovered the formula for a mirror black glaze even earlier when he was in Missouri, it was a conscious decision on his part not to use it in regard to the upper and lower fields which surround the broadly banded landscape of the University City serpent bowl. The color is a matte black which has undulations of glaze dripping down over the bowl's body. It is not the reflective black of his later success; rather it is a mysterious and impenetrable one which confounds and stops us from entering at the same time, like the inky fluid an octopus ejects when threatened, creating a filmy screen behind which it hides and then escapes from the scene. Notably, the serpent's head extends across the edge of the landscape's band into this blackness which leads to the mouth of the bowl; his long tail also enters into the dark field below the landscape and wraps itself firmly around infinity's dark side. Rhead is telling us something; his design is speaking for him: The snake's powers exceed the daylight in which it is seen by the viewer. It is a celestial or moral voyager, equally at home in the sunlight and in the surrounding darkness above and under it. Perhaps even more so in the darkness, as there are no clouds or grasses there-only the snake itself and the broad expanse of black. Rhead's artistry enforces the symbolism of the animal which predominates over everything else depicted on the bowl. Some American Art Pottery rises to the level of mythic representation as other great art does. In this instance, Rhead's adder in the bull rushes, like Van Briggle's despondency vase, is just such an example.

SOLD

Isak Lindenauer

Three examples of Trippett's Redlands pottery circa 1904

"W.H. Trippett, born in 1862, left New York state in 1895, evidently to find a healthier climate for his tuberculosis. He was a former art metal worker for Tiffany Studios, but experimented and was self-trained in ceramics for three years before opening his business out of his home on Summit Avenue in Redlands, California.

An early sales pamphlet, according to research by University of Redlands student Eric Boynton in 1993, elaborates: "About three years ago, while looking for a damp place where some tadpoles might continue their evolution , W.H. Trippett of Redlands happened upon a surface bed of damp clay."

"The "American Arts and Crafts, Virtue in Design" book notes that Redlands city directories list Trippett between 1902 and 1908 "first as a sculptor, then as an artist, and finally as a pottery proprietor However, a tile dated 1904 in a Redlands Pottery sales brochure suggests he was in business by that date, and a 1905 trade catalogue ...(shows that)... Trippett's wares were retailed that year in San Francisco (with the Paul Elder Company)."

Nelda Stuck Redlands Daily Facts 10/23.2010

Rookwood lidded jar with seahorses

Rookwood vellum pottery, lidded bowl with seahorse decoration by E.T. Hurley. Cincinnati, Ohio, dated 1901

bird tile by Van Briggle

Van Briggle tile of a bird on a branch. Colorado Springs, Colorado, circa 1910. unmarked. 6" diameter.

Rookwood vase with tiger decoration

Rookwood Standard glaze pillow vase with tiger decoration. Artist cypher "B or notation of "buff", the clay body. Cincinnati, Ohio, dated 1894

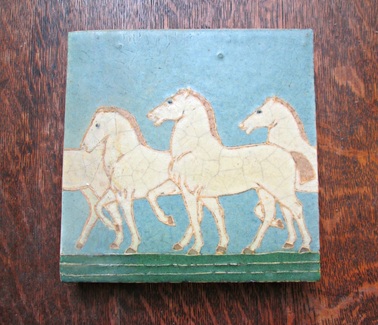

Grueby tile with horses

Grueby pottery tile with horses

Boston Massachusetts circa 1910

Rookwood with butterflies

Rookwood vellum vase with decoration of blue butterflies.

Cincinnati, Ohio. Artist: Lenore Asbury Dated 1918

Batchelder rabbit tile

Matte glazed rabbit tile by Batchelder

Los Angeles, California. circa 1915

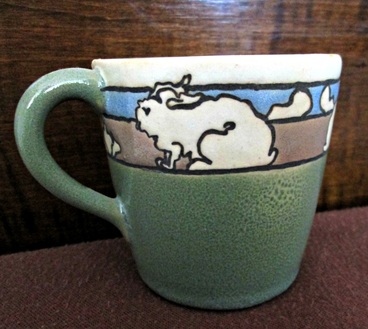

Saturday Evening Girls rabbit pitcher

Saturday Evening Girls creamer with decoration of rabbits

Boston, Massachusetts. Decorated by Sarah Galner, dated 1914

Rookwood jardiniere with four owls

Large Rookwood jardiniere with owls. Cincinnati, Ohio. Marked four times with the Rookwood cypher and the Roman numeral X for the year 1910, an "M" in a circle, and 1775Y. Diameter: 15" Height: 12"

Grueby tile with loons

Grueby tile with decoration of intertwined loons.

Boston, Massachusetts, circa 1905

rookwood vase with albatross

Sea green Rookwood vase with decoration of albatross over a stormy sea. Cincinnati, Ohio. Decorated by E.T. Hurley. Dated 1901 A "spiritual" vase if ever there were one!

low bowl by Walrath with frogs

Low bowl with trio of frogs on leaves by Walrath pottery.

Rochester, New York. 1900-1920

Rookwood vase with carp

Carved matte Rookwood vase with carp jumping out of an ocean wave. Cincinnati, Ohio. Decorated by Edith Noonan.

Dated 1908.

L. A. Pressed Brick Company bear tile

Rare bear tile with the words: Compliments of L. A. Pressed Brick Co. 8 1/2" diameter. Los Angeles, California circa 1912.

Newcomb College mug with turtles

High glaze Newcomb College mug with decoration of turtles. New Orleans, Louisiana. Decorated by Henrietta Bailey. Dated 1910.

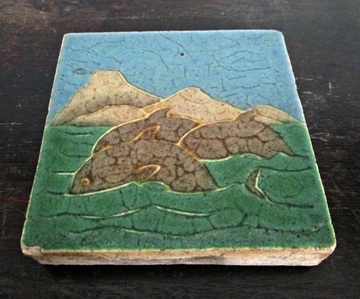

Grueby dolphins tile

Grueby tile with trio of dolphins cavorting. Boston, Massachusetts. Circa 1908.

Rookwood vase with swans

Tall Rookwood iris glazed vase with decoration of a pair of swans. Cincinnati, Ohio. Decorated by Carl Schmidt. Dated 1905.

McCusick tile with wolf

Gila tile with decoration of a howling wolf. Globe, Arizona, circa 1960. The McCusicks, Bob and Charmion, have worked in an essentially Arts and Crafts tradition creating tiles for four decades or more employing regional motifs. They have employed a number of Native American Navajo and Apache artists who have become famous in their own right for their artwork. He has a degree in Ceramic Engineering and owns a clay mine, where he mined the clay that he and his wife used to hand form and decorate tiles accurately depicting desert animals and plants and Native American motifs. Bob McKusick works with one arm, handy capable, which makes his work with clay all the more impressive. McKusick tiles, mosaics and murals are found in many homes and public buildings, and may be seen in a number of museums. Their family business was located in the foothills of the Pinal Mountains from 1949 to 1996.

Grueby scarabs

A group of Grueby pottery scarabs in a variety of colors.

Boston, Massachusetts. Circa 1908

California faience doves tile

Rare California Faience tile with three doves. Berkeley, California

circa 1918.

Rookwood with geese

Rookwood banded vellum vase with flying geese.

Cincinnati, Ohio. Decorated by Kitaro Shirayamadani. Dated 1909.

taylor parrot tiles

Taylor tile triptych of a macaw. Santa Monica, California

circa 1930.

Rookwood vase with grouse

Unusual iris glazed Rookwood vase with a wild grouse in the forest. Cincinnati, Ohio. Decorated by Grace Young. Dated 1904.

Mueller mosaic winged lion

Winged lion by Mueller Mosaic Tile Company. Trenton, New Jersey. circa 1908.

Bless the birds and the beasts. May humankind learn to honor their presence and save them from the worst of ourselves which does not steward them well these days...in the good caring of them and the rest of our planet rests our own future...

copyright Isak Lindenauer 2020-2025

copyright Isak Lindenauer 2020-2025