That Newcomb college vase which first took my breath away... (c. 1969)

That Newcomb college vase which first took my breath away... (c. 1969)

-

I soon began specializing in the Arts and Crafts in my shop. I had been walking around in student days looking at Julia Morgan buildings and Bernard Maybeck homes, not knowing who the architects were, but loving the style and beauty of their architecture. One thing led to another, and whether it was the very first piece of pottery I had purchased Way Back When at the Alameda Flea Market for seven dollars which turned out to be a Newcomb vase, or a serape, or a woodblock by someone named William Rice which I first sold for one hundred and forty-five dollars; these objects were works of art which I found appealing and knew I could bring to the shop and sell for a profit or keep and live with in my happy home.

I didn't know who made the Newcomb vase, or even that it was an example of Sophie Newcomb College pottery from New Orleans. (That knowledge was to come years later.) And it had a hairline! I knew however that I couldn't walk away from it. Each time I put it down and started to leave, I found myself stopping in my tracks and picking it back up again. It was the romantic South: the color which was twilight itself; the flowers ringed around its waist; that quiet time of reflection...

So of course I bought it. I left astonished that I had bought my first piece of pottery, something broken, luscious, seductive, and for so much money but, Hey... Yes, I still live with it.

A few years after opening my Berkeley shop, I went to see William van Erp at the last workshop's location on 14th Street in San Francisco. It was unbelievable to meet Dirk van Erp's son, to sit and watch him and Larry Roberts, the last worker at the workshop with William, as they both hammered and crafted trays and vases, boxes and lamps. I sat with stars in my eyes and a notebook on my lap, taking copious notes for oral histories. I wanted to record as much as I possibly could. I knew it was a privilege. They were both so great to me. William was in his seventies at that time and had difficulty with the circulation in his legs after long hours at the workbench. I used to bring him Epsom Salts when I visited. They both did a few jobs for me. I asked William if he would make a small lamp for me out of a vase, which he did. Then he made another for me some months later. I wanted to have van Erp lamps in my shop and they were impossible to find and costly even back then. William got angry with me when he found out I had asked him to make them so I could sell them in my shop. He had thought that I wanted them for myself. Well, of course, I did. But I wanted both to live with AND sell van Erp and have felt those twin desires ever since then. He had never considered anything but their ownership in people's homes and offices. It took him by unpleasant surprise but he came around. He decided I wasn't like some of the other dealers who only saw money when they saw the name "van Erp". I was genuinely nuts for the stuff. I kept and lived with van Erp as well and that ultimately re-assured him. He did other work for me thereafter. I will always be grateful for his having shared that remarkable opportunity--that time to sit in a workshop full of a hundred hammers, stakes, and files which were the essentials required to create their repertoire of the best copper ware of the Arts and Crafts, period. It was living history.

I soon began specializing in the Arts and Crafts in my shop. I had been walking around in student days looking at Julia Morgan buildings and Bernard Maybeck homes, not knowing who the architects were, but loving the style and beauty of their architecture. One thing led to another, and whether it was the very first piece of pottery I had purchased Way Back When at the Alameda Flea Market for seven dollars which turned out to be a Newcomb vase, or a serape, or a woodblock by someone named William Rice which I first sold for one hundred and forty-five dollars; these objects were works of art which I found appealing and knew I could bring to the shop and sell for a profit or keep and live with in my happy home.

I didn't know who made the Newcomb vase, or even that it was an example of Sophie Newcomb College pottery from New Orleans. (That knowledge was to come years later.) And it had a hairline! I knew however that I couldn't walk away from it. Each time I put it down and started to leave, I found myself stopping in my tracks and picking it back up again. It was the romantic South: the color which was twilight itself; the flowers ringed around its waist; that quiet time of reflection...

So of course I bought it. I left astonished that I had bought my first piece of pottery, something broken, luscious, seductive, and for so much money but, Hey... Yes, I still live with it.

A few years after opening my Berkeley shop, I went to see William van Erp at the last workshop's location on 14th Street in San Francisco. It was unbelievable to meet Dirk van Erp's son, to sit and watch him and Larry Roberts, the last worker at the workshop with William, as they both hammered and crafted trays and vases, boxes and lamps. I sat with stars in my eyes and a notebook on my lap, taking copious notes for oral histories. I wanted to record as much as I possibly could. I knew it was a privilege. They were both so great to me. William was in his seventies at that time and had difficulty with the circulation in his legs after long hours at the workbench. I used to bring him Epsom Salts when I visited. They both did a few jobs for me. I asked William if he would make a small lamp for me out of a vase, which he did. Then he made another for me some months later. I wanted to have van Erp lamps in my shop and they were impossible to find and costly even back then. William got angry with me when he found out I had asked him to make them so I could sell them in my shop. He had thought that I wanted them for myself. Well, of course, I did. But I wanted both to live with AND sell van Erp and have felt those twin desires ever since then. He had never considered anything but their ownership in people's homes and offices. It took him by unpleasant surprise but he came around. He decided I wasn't like some of the other dealers who only saw money when they saw the name "van Erp". I was genuinely nuts for the stuff. I kept and lived with van Erp as well and that ultimately re-assured him. He did other work for me thereafter. I will always be grateful for his having shared that remarkable opportunity--that time to sit in a workshop full of a hundred hammers, stakes, and files which were the essentials required to create their repertoire of the best copper ware of the Arts and Crafts, period. It was living history.

The courtyard, which in the day was filled with orchids on the left. The back, which was formerly a blacksmith's shop became the van Erp's office/storage area for work that was finished and ready to be picked up, also on the left. The right side was the workshop proper where William van Erp and Larry Roberts hammered away.

William van Erp gave me an orchid from the courtyard in front of the van Erp workshop, many years ago. I still have it in my garden.The business at the workshop was handled in the little front building, there was a driveway on the left, a courtyard filled with cymbidiums on the far left, and, in the back area on the left side, a little office and storage/pick-up area where customers who were having work done could collect their finished pieces. On the right side for the full length of the building out back was the workshop and a long bench down the middle of the room with tools and equipment lining the walls on three sides. It's at that long bench I got to sit, with old William van Erp and Larry Roberts, and talk about the shop's history and the art of hammering in metal.

Beyond words.

Young Dirk van Erp (c. 1881)

Young Dirk van Erp (c. 1881)

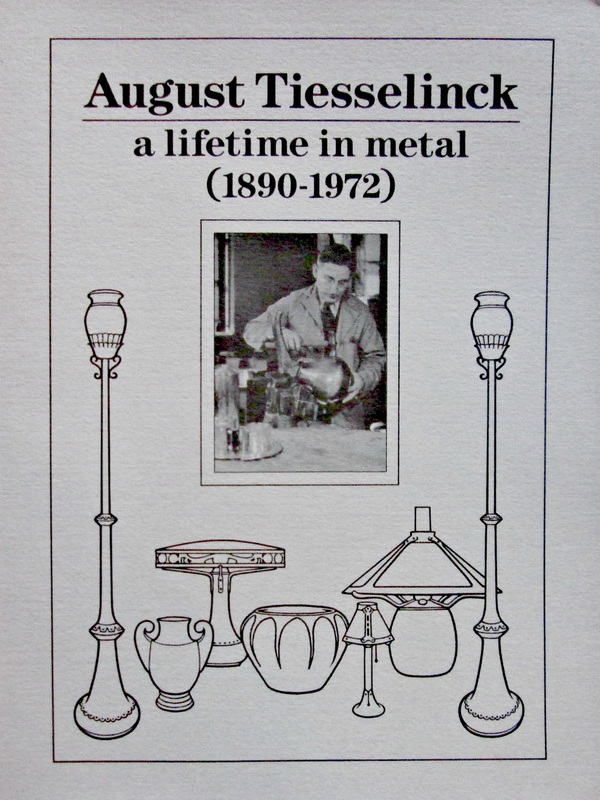

As I said, that was the beginning of my love for the work and the start of my research which years later led me to the discovery of the shop's foreman and chief instructor, van Erp's nephew, August Tiesselinck and led me to curate an exhibition in the shop of his lifetime in metal. That story involves two remarkable torchieres and I will share it at another time so as not to get too far off topic.That discovery led to other exhibitions: one on the work of Harry Dixon for the Sonoma County Museum in 1990 and to a second exhibit in my shop in 2015, twenty-five years after the first exhibit, also on the work of the van Erp studio. Along the way were many discoveries which I have happily shared with the public.

There was however one singular assertion by a complete stranger who came into my shop some thirty or so years ago that I have never spoken publicly about. What he had to say was challenging and was shared so earnestly, I had no reason to think he was not telling me the truth. As the years passed, I ultimately decided to share it myself, with a couple who do research in the field whom I respect highly and one other trusted friend, so that others might continue the investigation if I should die before I was able to discover whether or not it was true. No one else has heard what he told me until now.

It's a very odd thing but this last month I found myself thinking a great deal about my advancing years. They whiz by, and along with that awareness was the recurring thought that perhaps I should make public this assertion in an essay on my website.That way if I never got the time to investigate it further, at least someone else other than the people I had previously told in confidence long ago would hear it, and that might spark some future researcher's interest in hunting out more information. In spite of these thoughts, I still decided not to act and write the essay. And then....

The next week I was called to jury duty. After a lengthy selection process taking most of the morning, during which time the group was culled and culled again, I found myself sitting in a prospective juror's seat. I knew I would have to take a stand and make a personal statement about the upcoming trial. Each juror was questioned about his or her past history with the intent of discovering bias. A young man was up on two felony counts. He had stolen a car and then sold it. If convicted, prison was in his future.Three people claimed bias on the basis of having dealt in the recent past with car break-ins and thefts.The judge would not consider it as each had admitted to his followup question that it probably wouldn't affect their ability to decide impartially. I too had my truck broken into. I said as much. What I told the judge was the truth. I was trying everything to get excused from sitting in judgment of this young man. He said that wouldn't excuse me either and then asked the twenty-four of us directly if there were any other reason to be excused due to bias. No one made any attempt to respond and then I raised my hand.

"Your honor, I cannot put someone in prison." was what I said when asked. "Mr. Lindenauer, you must understand, the sole duty of the jurors is to listen to the evidence presented and decide on the basis of what they have heard as to the guilt or innocence of the person charged. The sentencing of someone convicted of a crime is a decision which rests in the sole purview of the judge." "Yes, your honor. but I cannot separate the two." My heart was racing as I was afraid I might be held in contempt. This selection process had started early in the morning and it was past noon at that point. "We will take a recess. I would like all the selected people to come back at two. Mr. Lindenauer, please return at one thirty."

So I sat outside for an hour and a half in the hall, sweating and worrying and wondering why I just couldn't shut up about it all and let "justice" take its course. Then I was called back in and told to sit back in the jury box in the empty courtroom with only the district attorney, the defense attorney, bailiff, the stenographer, and the judge. He addressed me, repeating where we had left off when he had called for a recess. He reiterated what had transpired earlier and then asked me if upon further consideration I had changed my position. No, I hadn't. I told the judge I had great respect for the court, that I was a peaceful man, but that I thought that the criminal justice system was broken; that it was punitive, not rehabilitative, that it was racist and classist. That a rich man got one sort of justice and a poor man got another, that prison had become a bizarre jungle of mayhem, rape, and murder, with terror everywhere, twenty-four/seven. And that I knew what I was talking about because my father had been in prison. That stopped the judge cold, and the attorneys, the bailiff, and the stenographer. He was a good judge. He had been measured, thoughtful, probing in his questions of all the jurors, and he heard me. After a considered silence, he said "If I am to understand you, Mr Lindenauer, you believe your thinking constitutes a bias which should excuse you from sitting on this jury." I wish I had had the presence of mind to say "A belief, your honor; not a bias." But rather than parse the meaning, I agreed. He turned to the two attorneys and said "Now both of you may ask Mr. Lindenauer any questions you may have; and when both declined, I was thanked for my service, excused, and as a final statement the judge said he hoped I would serve in the future on a civil case. And, thankfully, having been excused, I left.

That was an extremely difficult day for me. The events had brought up a great deal from my family's past and I had passed a personal test in the process. Perhaps many will think that all of this I have shared as a prologue to what will soon follow is irrelevant. For me, these facts represent an invisible force which runs through events in my life. Five days later, the information I had been hunting for--for more than thirty years--was suddenly right before my eyes. Since I have spent all that time searching, I hope it will not seem unreasonable that I have wanted to take five minutes of your time to tell my story in addition to now telling you what was revealed to me. Perhaps after reading what follows, you will understand why I marvel at the manner and sequence in which all of this has come to pass.

What I was told long ago was the following: That Dirk van Erp had to leave Holland.That as a young man, he and a couple of other fellows had gotten involved in something against the law and that van Erp had perjured himself while giving testimony in court. That those events brought dishonor upon him and his family and the young van Erp eventually decided to leave Holland, to set out on his own and attempt to make a new name for himself in a new land.

I had always wanted to go back to Holland to see if I could confirm whether or not the statement was true, but that had yet to happen.

Now, after the passing of so many summers and winters and quite by accident or cosmic intent, a week or so ago, while continuing to search for new information on the old topic, I came across a text which opened the locked door to van Erp's past. I made contact with Karleen Veenker who had written it and she shared with me an article written by a Dutch historian, Lutske Vlieger. A startlingly dramatic story unfolded which I could never have imagined in my wildest dreams. Herein the mysterious truths of the old story are clarified and resolved. I share it with you readers--the strange tale which I came upon so unexpectedly, after literally decades of searching. It is excerpted here from the article by Lutske Vlieger which goes on to talk about van Erp's later life in America as a copper smith after arriving here from Holland.

What follows is an excerpt from an original article by Lutske Vlieger, archivist at Historisch Centrum Leeuwarden ( The Netherlands) first shared with me by Karleen Veenker whose great grandfather was Dirk van Erp's brother, translated from the Dutch by Alan Thomsen.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

"Dirk Van Erp, from Crook to Copper Artist"

by Lutske Vlieger

"Between 1882-1896 the Secret Registry of Released Prisoners was in use. This Registry contained "carte de visite portraits", personal information and the criminal record of prisoners. Recidivists from the prison in Hoorn, Leiden, 'sHertogenbosch, Rotterdam and Utrecht who had received a jail time of 2 years or more in a community prison or a single year of solitary confinement were added to the Register. Also, all released prisoners from the Leeuwarden prison were noted in the Register. At the end of the 19th century the Leeuwarden prison housed mainly serious criminals with jail time longer than 5 years. One of the released prisoners was Dirk van Erp, the son of copper smith Willem van Erp, who had settled in 1857 in Nieuwestad.

Attempted Theft and Bribery

It was a cold Saturday afternoon in February 1881 when 19 year old Dirk van Erp rang the doorbell at the front door of Minister Sije Cornelius Thoden van Velzen. Dirk did not spontaneously show up at the minister's stoop, he was sent by chimney sweep Joannes Baptista Beltrami to collect something. Beltrami informed Mrs. Thoden van Velzen by way of a threatening letter that he would kill her if she would not pay him 5000 Dutch Guilders. Beltrami happened to know that Mrs.Thoden van Velzen gave birth to an illegitimate child at the age of 20 and Beltrami wanted hush money.

Beltrami wanted to receive the money in 100 Guilder banknotes, wrapped in paper. Mrs .Thoden van Velzen had prepared a paper package in consultation with the police. However the package did not contain banknotes but a bible. Dirk picked up the package, but returned it within the hour because he could not find Beltrami.

A few weeks later another letter was written to Mrs. Thoden van Velzen by Beltrami. This letter was far more grim than the first one. Beltrami called Mrs. Thoden van Velzen a cursed woman and informed her that he initially would have strangled her and her husband, but it was too dangerous. He requested the money again, because he wanted it, "even if that meant he needed to commit 20 murders."

As far as is known, the money was never paid. After the second letter was received, another package was prepared but never collected. It is said that Beltrami wrote the letter out of revenge. In 1880 he was fired as chimney sweep by Mrs. Thoden van Velzen and she refused to pay the invoice for that year.

In the night of December 24th, 1881, a second crime took place at a house on the Harlingersingel. Dirk and Beltrami agreed to break into the house of 79 year old widow Rinske van der Werff to steal money and goods. The widow's ill health did not stop them. Once they arrived at the house, Beltrami climbed on the roof and smashed the attic window. Dirk was standing guard and was to sound the alarm if needed. He was also in charge of holding the door on the street side so that no one could leave the property. Dirk was concerned about foot traffic passing by and moved a bit away from the house. A housemate of the widow heard noises on the roof and heard the glass of a window shatter. She began to scream and Dirk and Beltrami escaped, again without any proceeds from their attempted theft.

If the first 2 attempts were not enough, on Friday January 6th, 1882, Dirk and Beltrami, together with watchmaker Petrus Zeiss, headed to the house of 84 year old widow Nijhoff at the corner of Beijerstraat and Muggesteeg. That afternoon in the Warringa's Inn, they had devised a plan to steal money (if needed, by force). Beltrami knew the house because he had cleaned the chimney there.

Dirk was standing guard, when Beltrami and Zeiss rang the widow's doorbell. They handed the maid who opened the door the prepared envelopes with the request to put the money in there.The maid brought the envelopes to the widow and Beltrami followed her, armed with an ax. Petrus Zeiss waited outside. Under the threat of Beltrami, the widow put 8 "rijksdaalders" (large silver coins) in the envelopes. Beltrami left after threatening the maid not to follow him, or else "bad things would happen."

Even though Dirk was supposed to wait in the Beijerstraa location, in order to be able to give Zeiss a signal if the police showed up, after the front door closed he moved to the square at the "Grote Kerk" (big church). The police station was located in the Beijerstraat and most likely Dirk left out of fear of the police showing up.

After Beltrami joined Dirk and Zeiss, they shared the money. Dirk received in total 8 guilders, Beltrami got rid of the ax by dumping it in an ashcan in the Poptasteeg (street name). A witness later declared that he found an ax at that location.

January 8, Joannes Baptista Beltrami, Petrus Zeiss, and Dirk van Erp were arrested. At the time of the arrest, Dirk still carried 3 guilders and 65 cents. The rest of the money had been spent at a tobacco shop and at inns.

On January 9th, 1882, he was registered at the "house of arrest" as 1.76 meteres tall, brown hair, brown eyes, oval face, round forehead, and a small scar on his nose.

During the hearing, 17 witnesses made a declaration. On May 17, 1882. Dirk was convicted of:

-Attempted theft at night by 2 people in an occupied residence by way of breaking and entering.

-Complicity by fencing the stolen goods.

In prison, Dirk was a tinsmith, the trade he learned from his father. A document by Kooperbergs named "Medical Topography of Leeuwarden 1888" proves that law and order prevailed at the prison. The prisoners spent 4.5 hours daily in the residence halls, of which time they ate for 1 hour and walked the court yard for 1 hour. They spent 10 hours in the work rooms, working on trades like book binding, tailoring, carpentry, and smithing. From 9pm until 5:30 am the prisoners were in the dorms. they ate 3 times a day, bread and coffee for breakfast and supper and a hot meal was served for lunch. Smoking was only allowed in the court yard. Dirk was well- behaved in prison, which was noted in the Registry. He was released from the Leeuwarden prison 3 months early on February 16, 1887....

After his release from prison, Dirk first lived in Leeuwarden for a while, presumably with his parents. He thereafter changed course. He headed to Vlaardingen in 1889, and subsequently departed by sea from Rotterdam to America. Dirk arrived, with three pieces of baggage, in New York Harbor on October 6th, 1890. It was not unusual at that time for Frisians to depart for America. Economic conditions in the Netherlands were bad on account of the agricultural crisis. Poverty reigned and America offered opportunities. It does not seem unlikely, however, that Dirk’s past played a role in his decision to leave.

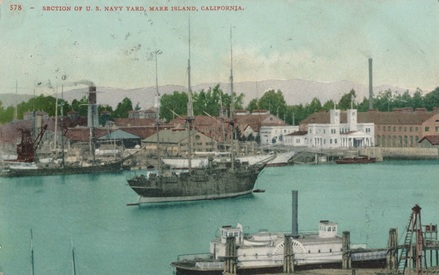

Once in America, an entirely different life began for Dirk van Erp. He became a coppersmith at Union Iron Works, a large firm in San Francisco which among other things produced railroad and agricultural equipment and was also well known as a shipyard. Dirk also became acquainted with Mary Richardson, a divorced woman with three children. They got married and had two children together: Agatha and William.

In 1898 Dirk tested his luck during the Klondike Gold Rush in Alaska’s Yukon. After gold was discovered in Bonanza Creek in 1896, thousands of people headed to this spot. Dirk also caught gold fever and sought to get more out of life by amassing a fortune. Alas with all the gold hunters, the reserves of gold quickly ran out and such money was not to be had by Dirk. From letters sent to his family in the Netherlands, it seems the trip to Alaska must have been quite difficult. Many men lost their lives during the harsh journey over the ice. Late in 1898, at the urgings of Mary, Dirk returned home."

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

The rest of the article, as I have said, deals with van Erp's life in America where he sought his own redemption and ultimately became an art copper smith of ever-growing distinction. I intend to post more information in the following weeks which includes a family chronology with many pictures and individual histories of family members and will continue investigating the events which have been documented in the Vlieger article.

I imagine many readers are as surprised as I was to read the story of van Erp's crimes and incarceration. I have not published this to denigrate Dirk van Erp, but rather to expand our knowledge of him and his life in an attempt to get a fuller picture, and as a result, a deeper understanding as to what might have motivated him to accomplish much of what we have come to know in his later life. This arrest was clearly a pivotal point in his life.To keep silent about it now that it has been well-documented by one of Leeuwarden's

leading historians would be to leave everyone in America with an incomplete picture of the man. To omit it would ironically perpetuate the stigma by leaving it behind, apart from him in the darkness. I would prefer to present any and all information I know of and give others the opportunity to draw their own conclusions after it has been unknown history for over one hundred years.

This story raises as many questions as it answers: Who was Beltrami? How did Dirk meet him? What drove him to involve himself in such activities? His family was not exceedingly wealthy but neither were they impoverished. Were these desperate acts caused by some other as of yet unknown need for money or risk? Van Erp seems somehow ancillary to the more criminal acts committed by Beltrami, yet clearly he was an active, if nervous, participant. Why would he take such chances and commit such crimes repeatedly, risk his freedom and his future? To these questions and more, I, for one, want to find answers.

I draw a great deal from this surprising tale. Van Erp's drive to succeed, to make a new, good name for himself seems inextricably linked to his past criminal activity in Holland. I imagine he must have felt contrite and determined to undo any harm he may have brought to his family. This is in part suggested by his striving to become well-recognized, highly thought of, and financially successful in his career in Art Copper. All these things he managed to achieve after coming to America. His time in and his release from prison was undoubtedly the major impetus which propelled him forward from the last years of his youth in Holland. His determination to seek out wealth by hunting for gold in Alaska, a voyage fraught with real life and death perils at every turn is re-framed, his motive amplified and must be viewed in a different light. For hundreds to have started out to "strike it rich", for so many to have died of sickness along the way, for hundreds to have died, buried alive in avalanches during the hunt underscores just how grim and indomitable his drive was, even so far as to take such great risks with his own life, all in the sole hope of finding gold. That hunt takes on a hyper-symbolism all its own, beyond the geologic, when we consider it now.

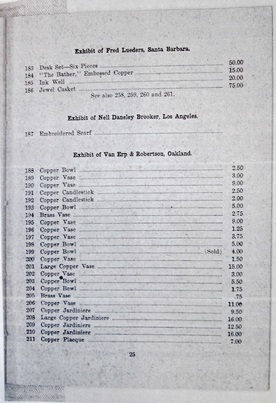

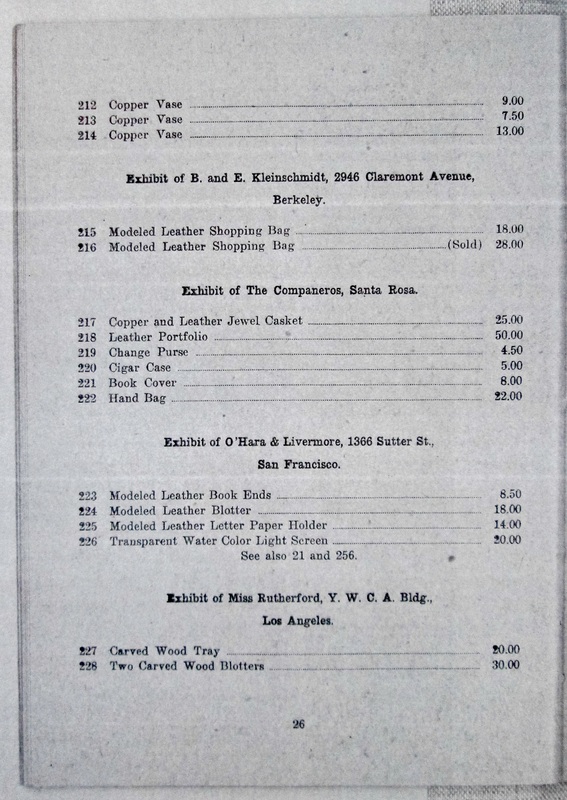

The failed trip to Alaska led to his hammering vases at the Mare Island shipyards where he worked after coming home. That endeavor was the beginning of his crafting Art Copper and his return to Seattle in 1909 to exhibit his wares at the Alaska-Yukon Pacific Exposition. It was there he met his future business partner, Eleanor D'Arcy Gaw, who was showing her metalwork. Other exhibitors included Elizabeth Eaton Burton and her father Charles Frederick Eaton of Santa Barbara and Albert Berry who worked in Juno, Alaska before relocating to Seattle. So van Erp was exposed to men and women who were on their way to becoming some of the leading crafters of his time as well as a woman with whom he would associate in business the very next year. D'Arcy Gaw helped van Erp transition from his copper shop in Oakland to their shop together in San Francisco.That brief association brought them both business and acclaim. Had van Erp not been incarcerated in Holland as a young man, it is probable that he would not have emigrated to America. As Vlieger noted earlier, most northern Dutch immigrants at the end of the nineteenth century left for America because of desperate economic conditions in the agricultural sector. Van Erp however, hailed from an established, prosperous merchant and craft milieu. His economic situation was not at all dire, unlike most who emigrated. Taking this into consideration, it seems much more likely that he would have remained in Holland working in his family's shop and living a quiet life of peace and prosperity at home. He may otherwise never have had the level of success he reached here after his life had been irrevocably altered by his years in prison.

Of course, we may never get answers to this conjecture or any confirmation on the accuracy of these musings, but it does seem reasonable to acknowledge these remarkable and fateful events in his life and their effects; his trials as well as his successes. Together, they shaped the character of the man and the innovative artisan/artist he eventually became.

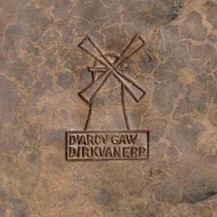

The rare D'Arcy Gaw/Dirk van Erp hallmark used for less than a year, most of 1910.

The rare D'Arcy Gaw/Dirk van Erp hallmark used for less than a year, most of 1910.

An indication of his intense drive to be recognized is the proprietary nature of his product. After 1910, his metal work is always marked with his full name and only his name along with a windmill. Ironic, this reference to his homeland. How much it must have meant to him and how poignant to us that he incorporated this symbol which is so emblematic of his homeland and intentionally struck it on every piece as the primary identifier above his own name. He may have felt compelled to leave Holland, but once free and in America, he could not be forced to deny his homeland or his birthright if he chose otherwise. While many others worked at the studio over the years, it is only the name of his first partner "D'Arcy Gaw" in San Francisco, which ever appears for almost eight months of 1910 on the first work produced by them during that brief tenure. Thereafter it is almost always his name and his alone on the work with a few rare exceptions. So powerfully transmitted was this sense of his dominance and importance that long after he had died, his son William signed his work invoices with his father's name and answered to that call by others.The name of the workshop / studio never changed in the forty-three years William continued at the helm after his father had retired in 1929 and then passed away in 1933. It had become a brand of distinction.

I have never heard anyone other than the person who mentioned a sinister past to me refer to any difficulties Dirk van Erp may have had before he came to California. But we are left with the legacy of that powerful, personal history which must certainly have loomed heavily, even if seen by no others, over van Erp's own head and heart for all his days.... He returned to Holland only once after coming here, after his mother had died in 1908. (His father had passed away in 1900.) Even then, having returned home, he could not show his remaining family that he had made a great success of himself in America. Both of his parents were gone and that success was not far away, but it still remained ahead of him. By that time he had opened a new shop in Oakland and was experiencing a good amount of popularity with "carriages of the wealthy pulling up to his front door " and well-known shops in San Francisco were offering his wares for sale there too. How hard it must have been to bear, to have left his homeland having tarnished his family's good name, only to return too late to share with his parents the level of success he was experiencing so soon after their deaths. At least he could speak to the rest of his family of the real promise his new career in copper was beginning to manifest.

I want to go to Holland to flesh out this story even more. I want to see what further answers I can find, what other details provide us with a deeper understanding of the forces which may have been at play: familial, social, circumstantial, all informing this new chapter I am now writing about after a century or more of Americans' fascination with this enigmatic man and his craft. To learn more about the testimonies given during the trial, to find out more about this dark character, Beltrami, to perhaps read in newspapers of the day how the events were reported. All of these aspects remain so intriguing and potentially informative. What a challenge it would be to do further research to deepen our understanding of van Erp's life as a young man in Leeuwarden.

I don't think finding out this troubled past diminishes his character to any great or lasting degree. I don't excuse what he did, nor do I minimize it. I think he was involved in terrible criminal activity and he was lucky that the ringleader, Beltrami, didn't take more violent action beyond his threats and weapons, raising the level of their felonies because of greater violence, even ax murders. It is frightening to admit that Beltrami sounds as though he was capable of having done just that. Van Erp comes off as a bit of a skittish "second" during most of the attempts. But he did participate repeatedly and profited from their crimes, and he was judged and sentenced and paid the penalty for them.

It sounds as though van Erp came out of the penitentiary a changed man. He lived in Holland about three years before leaving for America, I believe he developed a new determination which became the hallmark of his ensuing years as much as the windmill was the symbol he struck on all his work thereafter. He was a proud Dutchman no matter what; Hollander first and last. I think in a strange way, it adds a degree of romantic heroism to his life. We can't measure the regret, but it is there. We can't know if he felt remorse, but keeping the past such a secret is quiet testimony to the fact that was there too. Ironically, he is not "reduced" in my eyes by his past criminal behavior; rather he bears its marks and is metamorphosed by the fire, changed as is copper itself when it is heated and softened. Malleable then, it can become something else, something wonderful through art and craftsmanship. Dirk van Erp's fame and his high artistic accomplishments were forged in the crucible of his struggles to overcome the mistakes of his youth. And he too was changed by the fire....

I have never heard anyone other than the person who mentioned a sinister past to me refer to any difficulties Dirk van Erp may have had before he came to California. But we are left with the legacy of that powerful, personal history which must certainly have loomed heavily, even if seen by no others, over van Erp's own head and heart for all his days.... He returned to Holland only once after coming here, after his mother had died in 1908. (His father had passed away in 1900.) Even then, having returned home, he could not show his remaining family that he had made a great success of himself in America. Both of his parents were gone and that success was not far away, but it still remained ahead of him. By that time he had opened a new shop in Oakland and was experiencing a good amount of popularity with "carriages of the wealthy pulling up to his front door " and well-known shops in San Francisco were offering his wares for sale there too. How hard it must have been to bear, to have left his homeland having tarnished his family's good name, only to return too late to share with his parents the level of success he was experiencing so soon after their deaths. At least he could speak to the rest of his family of the real promise his new career in copper was beginning to manifest.

I want to go to Holland to flesh out this story even more. I want to see what further answers I can find, what other details provide us with a deeper understanding of the forces which may have been at play: familial, social, circumstantial, all informing this new chapter I am now writing about after a century or more of Americans' fascination with this enigmatic man and his craft. To learn more about the testimonies given during the trial, to find out more about this dark character, Beltrami, to perhaps read in newspapers of the day how the events were reported. All of these aspects remain so intriguing and potentially informative. What a challenge it would be to do further research to deepen our understanding of van Erp's life as a young man in Leeuwarden.

I don't think finding out this troubled past diminishes his character to any great or lasting degree. I don't excuse what he did, nor do I minimize it. I think he was involved in terrible criminal activity and he was lucky that the ringleader, Beltrami, didn't take more violent action beyond his threats and weapons, raising the level of their felonies because of greater violence, even ax murders. It is frightening to admit that Beltrami sounds as though he was capable of having done just that. Van Erp comes off as a bit of a skittish "second" during most of the attempts. But he did participate repeatedly and profited from their crimes, and he was judged and sentenced and paid the penalty for them.

It sounds as though van Erp came out of the penitentiary a changed man. He lived in Holland about three years before leaving for America, I believe he developed a new determination which became the hallmark of his ensuing years as much as the windmill was the symbol he struck on all his work thereafter. He was a proud Dutchman no matter what; Hollander first and last. I think in a strange way, it adds a degree of romantic heroism to his life. We can't measure the regret, but it is there. We can't know if he felt remorse, but keeping the past such a secret is quiet testimony to the fact that was there too. Ironically, he is not "reduced" in my eyes by his past criminal behavior; rather he bears its marks and is metamorphosed by the fire, changed as is copper itself when it is heated and softened. Malleable then, it can become something else, something wonderful through art and craftsmanship. Dirk van Erp's fame and his high artistic accomplishments were forged in the crucible of his struggles to overcome the mistakes of his youth. And he too was changed by the fire....

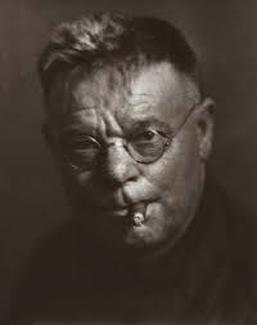

Dirk van erp c. 1920

Dirk van erp c. 1920

Ultimately, Dirk van Erp proved himself to be of lasting worth, a loving family man, a consummate crafter, and an artist whose work is highly considered and valued greatly. It will surely abide.The redemption he found imparts to his life story a richer, deeper meaning. I find it to be an inspiring one. I would like to thank Karleen Veenker and her aunt again for their insatiable curiosity to find out more about Dirk van Erp, the "unknown" family member in the iconic picture they had found of him with his cigar, and laud the remarkable, detailed research of archivist/historian Lutske Vlieger which Karleen shared with me. Now we can begin to embrace Dirk van Erp in the fullness of his truth. This is not the end to his story.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

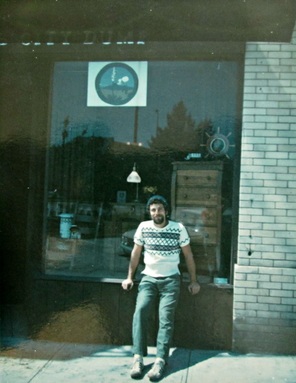

Me in the early years at the front door to my shop in the city when my hair was still brown! (c. 1985)

Me in the early years at the front door to my shop in the city when my hair was still brown! (c. 1985)

POSTSCRIPT ( A further personal memoir of sorts )

A story has been going around the Bay Area for a while now told by a local antique dealer who claims that when he was just a teen, he was writing a term paper for his high school on Dirk van Erp but couldn't find any other information on him besides the small section in the exhibition catalog for the show in Pasadena called California Design 1910. So he asked a San Francisco antique dealer to share more information than was readily available. He said something to the effect of: No way, kid. Why should I give you information when I can purchase lamps worth seven thousand dollars for one thousand dollars? Lots of luck!

A story has been going around the Bay Area for a while now told by a local antique dealer who claims that when he was just a teen, he was writing a term paper for his high school on Dirk van Erp but couldn't find any other information on him besides the small section in the exhibition catalog for the show in Pasadena called California Design 1910. So he asked a San Francisco antique dealer to share more information than was readily available. He said something to the effect of: No way, kid. Why should I give you information when I can purchase lamps worth seven thousand dollars for one thousand dollars? Lots of luck!

Picasso, The Bathers. 1918

Picasso, The Bathers. 1918

Since there are no other dealers with shops dedicated to the Arts and Crafts left in San Francisco any more, by inference most people may assume I am the one who said this. For the public record, I did not, nor anything like it. I trust those who know me would say it doesn't sound like me at all. At the time this was supposedly said there were other Arts and Crafts dealers in the city; and, if said, I imagine one of them is responsible for having said it. I have my suspicions. I don't dwell on this being passed around even though it is harmful to me. You can't stop people from saying things about you or others, good or bad. You have to be able to look at yourself in the mirror. That's the main thing. The rest is just talk which affects us all positively or adversely; high praise or malicious chatter, true or false. And people love to talk, right? So it has been and so it will probably always be.

As for me and my desire to profit from the sale of items from the workshop inordinately or otherwise, I can honestly say that while on rare occasions I have sold pieces for great amounts, there are a goodly number of contemporary crafters who are making objects which reflect the design vocabularies of the past who have made a great deal more on their reproductions than I have ever made selling the originals. My desire for profit has always been subordinate to my desire to gather and own. And I can recall many times early on when I spent everything I had to purchase an object made by the studio and workshop of Dirk van Erp or an associate: a chrysanthemum stencil bridge lamp, the Tiesselinck torchieres, and in later years, the large red warty lamp I still live with. Actually so many more pieces, it's embarrassing to admit. The sublime Greene and Greene cabinet which belonged to Charles Greene all his life, the Nobscot Grueby sign, a copper and abalone charger...and the stories related to each of these is wonderful and strange. I hope someday to write these stories down to share with you. I should have a tattoo on my arm which says: By things "possessed". Maybe "obsessed"? Or even "caressed"? Yes, all of them. I am a passionate spendthrift where these and other great objects are concerned. I say I am a happy, indentured servant living on the edge of my business. Sans souci. Without a care... A sale may be a necessary thing from time to time but is mostly secondary to me.

I would have loved a partner in life and, especially, I would loved to have had children. But in my own instance, my singularity leaves me without the need to support others which for most is a real and ever-present consideration. Not being responsible for a nuclear family's needs, if I have any way of purchasing those objects of virtue when I see them--to gather them for some particular intent like a future exhibition or simply because I hope to live with them for a long time, I tend to exercise that option. Certainly, profit is a consideration but I am not a dealer first. My occupation has always been more of an art form than it is a business. And while I rarely have great amounts of money for long as beautiful things continue to appear before me, somehow more money always comes. There is little doubt that living so close to the edge is not for everyone, but living this way has been such a worthwhile struggle for me because it has also given me great personal freedom to be myself in the mix. I'm not great at business. I'm okay at it. More than being a great businessman, I am an appreciator of great art.... I think of standing in front of two Gauguin's at the De Young in the middle of a French Impressionist show there. One was of a tree-lined road by a stream, its path leading to a house; the other, a view down a mountain gorge with a path to the ocean through its center. I had never known of the existence of either painting and I love Gauguin. I stood there looking, tears streaming. I did the same thing at the Museum of Modern Art in New York many years ago. There was a special exhibition called Picasso and Portraiture. Of the many great artists in the world, I am perhaps most taken by Picasso. I was overwhelmed again by art at the De Young three or four years ago when two of my very favorite Picassos were in front and in back of me at the same time in one of the rooms, a massive woman in a robe sitting in deep thought and a group of women bathers, at the seashore in brilliant suits and skewed angles of happiness. I couldn't stop talking about them to strangers around me, energizing them to see what I saw. I left the room and came back to it again because one viewing was not enough. One was so much smaller than I had ever imagined it would be; the other, conversely, was incredibly much larger.

As for me and my desire to profit from the sale of items from the workshop inordinately or otherwise, I can honestly say that while on rare occasions I have sold pieces for great amounts, there are a goodly number of contemporary crafters who are making objects which reflect the design vocabularies of the past who have made a great deal more on their reproductions than I have ever made selling the originals. My desire for profit has always been subordinate to my desire to gather and own. And I can recall many times early on when I spent everything I had to purchase an object made by the studio and workshop of Dirk van Erp or an associate: a chrysanthemum stencil bridge lamp, the Tiesselinck torchieres, and in later years, the large red warty lamp I still live with. Actually so many more pieces, it's embarrassing to admit. The sublime Greene and Greene cabinet which belonged to Charles Greene all his life, the Nobscot Grueby sign, a copper and abalone charger...and the stories related to each of these is wonderful and strange. I hope someday to write these stories down to share with you. I should have a tattoo on my arm which says: By things "possessed". Maybe "obsessed"? Or even "caressed"? Yes, all of them. I am a passionate spendthrift where these and other great objects are concerned. I say I am a happy, indentured servant living on the edge of my business. Sans souci. Without a care... A sale may be a necessary thing from time to time but is mostly secondary to me.

I would have loved a partner in life and, especially, I would loved to have had children. But in my own instance, my singularity leaves me without the need to support others which for most is a real and ever-present consideration. Not being responsible for a nuclear family's needs, if I have any way of purchasing those objects of virtue when I see them--to gather them for some particular intent like a future exhibition or simply because I hope to live with them for a long time, I tend to exercise that option. Certainly, profit is a consideration but I am not a dealer first. My occupation has always been more of an art form than it is a business. And while I rarely have great amounts of money for long as beautiful things continue to appear before me, somehow more money always comes. There is little doubt that living so close to the edge is not for everyone, but living this way has been such a worthwhile struggle for me because it has also given me great personal freedom to be myself in the mix. I'm not great at business. I'm okay at it. More than being a great businessman, I am an appreciator of great art.... I think of standing in front of two Gauguin's at the De Young in the middle of a French Impressionist show there. One was of a tree-lined road by a stream, its path leading to a house; the other, a view down a mountain gorge with a path to the ocean through its center. I had never known of the existence of either painting and I love Gauguin. I stood there looking, tears streaming. I did the same thing at the Museum of Modern Art in New York many years ago. There was a special exhibition called Picasso and Portraiture. Of the many great artists in the world, I am perhaps most taken by Picasso. I was overwhelmed again by art at the De Young three or four years ago when two of my very favorite Picassos were in front and in back of me at the same time in one of the rooms, a massive woman in a robe sitting in deep thought and a group of women bathers, at the seashore in brilliant suits and skewed angles of happiness. I couldn't stop talking about them to strangers around me, energizing them to see what I saw. I left the room and came back to it again because one viewing was not enough. One was so much smaller than I had ever imagined it would be; the other, conversely, was incredibly much larger.

Picasso, Seated Woman. 1920

Picasso, Seated Woman. 1920

But back to the Picasso and Portraiture exhibit in New York. My oldest friend, Jimmy, and I went. He had broken his leg so I wheeled him through the exhibition in a wheelchair. Crazy. The place was packed with people.The show was a maze of small and large rooms and in the middle of it all was a small, octagonal room as I remember and on the far wall as we stopped in the center of the room with people milling all around us, was a large white canvas. It was Dora Maar, his lover at the time, in bed. White bed sheets, white woman, white walls, everything white and suddenly I was crying again. Stupid. Couldn't help myself. I was Picasso in that room, looking at my love and everything was pure and full of the white light of that love.

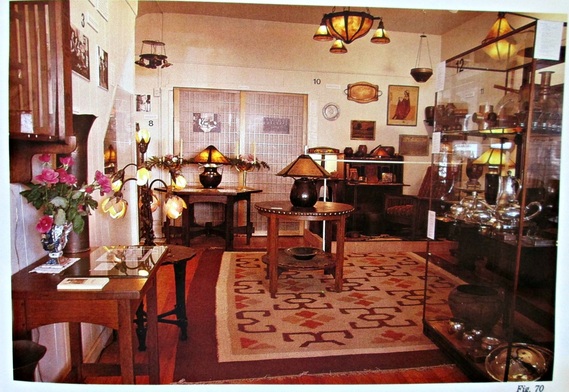

Inside my front door to the shop at 4143 19th Street.

Inside my front door to the shop at 4143 19th Street.

. I can never forget it. Everything else faded away, as it does, when we are in the presence of great Art... I'm an empathic soul, I suppose, a terrific audience, an eternal devotee. I say a slave to phantom beauty. Could there be anything better? Since the world is rich with great Art and beauty, I have these out of body, aesthetic, spiritual experiences again and again....

In later years, I would go back to the studio/workshop on Fourteenth Street, watching to see its ensuing incarnations. I always hoped the person who purchased the building would put a little museum in the front, dedicated to celebrating the Studio's work, and then keep the Workshop in back, functioning, with scholarships yearly to promising metal workers who could experience the thrill of working in that space. It was not to be. I later hoped to rent the front space to make a little museum as tribute to the van Erps. That also has never happened. I have tried a number of times as the front space has become a succession of shops changing over the years, an antique shop, a bicycle store, a flower shop.

The Workshop out back was torn apart and was extensively re- modeled into a modern, streamlined area for a group of dentists. One day, a decade or more ago, as I made yet another pilgrimage to the spot, I looked in the back down the driveway, and the work to dismantle the workshop had begun. I walked back to where the laborers were sledgehammering away the pavement at the entrance. At their feet was a pile of three or four horseshoes so I asked what was that all about. They said that as they began to demolish the building, it became clear that before the van Erps had occupied the space, in "days of yore", it had been a blacksmith's shop. The horseshoes they had been digging up were evidence of that prior industry. Of course, I pleaded with them for one, made known to them my long term caring for the work of the studio and the history of it as well, and they gave me one of them which to this day I have over the front door of my shop.

In later years, I would go back to the studio/workshop on Fourteenth Street, watching to see its ensuing incarnations. I always hoped the person who purchased the building would put a little museum in the front, dedicated to celebrating the Studio's work, and then keep the Workshop in back, functioning, with scholarships yearly to promising metal workers who could experience the thrill of working in that space. It was not to be. I later hoped to rent the front space to make a little museum as tribute to the van Erps. That also has never happened. I have tried a number of times as the front space has become a succession of shops changing over the years, an antique shop, a bicycle store, a flower shop.

The Workshop out back was torn apart and was extensively re- modeled into a modern, streamlined area for a group of dentists. One day, a decade or more ago, as I made yet another pilgrimage to the spot, I looked in the back down the driveway, and the work to dismantle the workshop had begun. I walked back to where the laborers were sledgehammering away the pavement at the entrance. At their feet was a pile of three or four horseshoes so I asked what was that all about. They said that as they began to demolish the building, it became clear that before the van Erps had occupied the space, in "days of yore", it had been a blacksmith's shop. The horseshoes they had been digging up were evidence of that prior industry. Of course, I pleaded with them for one, made known to them my long term caring for the work of the studio and the history of it as well, and they gave me one of them which to this day I have over the front door of my shop.

Isak Lindenauer

4143 19th Street

San Francisco, California

94114

415 552-6436 email: [email protected]

If you'd like to be on a list to receive updates

about new inventory and special shop events, or if

you have particular "wants" to fill out your home, business,

or specific collection, please use the contact form on this

site and send me an email with your email address and

any other pertinent information.

Copyright © 2014-2021, 2020-2025

Isak Lindenauer

4143 19th Street

San Francisco, California

94114

415 552-6436 email: [email protected]

If you'd like to be on a list to receive updates

about new inventory and special shop events, or if

you have particular "wants" to fill out your home, business,

or specific collection, please use the contact form on this

site and send me an email with your email address and

any other pertinent information.

Copyright © 2014-2021, 2020-2025

Isak Lindenauer