|

Essay Number Six September 20, 2014 MILK (No, not San Francisco's LGBT pioneer...) Certain things speak to me; I am drawn to them and they are drawn to me. I laughingly refer to myself as a thing magnet. I am pulled to objects, a slave to phantom beauty. I see something great, off go the antennae, and, bang, I connect. |

And whether it is the "lost" Grueby iris bathroom , Charles Greene's wondrous cabinet which he kept all his life and used in his office, the Nobscot Mountain Tea House double-sided Grueby sign, or an iconic California pot by Frederick Hurten Rhead-- in years past all called out to me, I purchased them, and they eventually became high points in my professional life. This is also true of many other things which have passed through my hands over the last forty years. In good humor about what I refer to as the exquisite curse I often say, "On one shoulder is tattooed "By things possessed", and on the other, "Shopping is my life." Joking aside, I have had meaningful and fulfilling relationships with objects, studying them, researching their histories and working to eventually see them go to a place where they will be held in the highest regard-whenever that was possible. Where the Nobscot sign was concerned, it took fifteen years and ultimately the help of some valued friends who are top notch researchers as well to finally locate The Nobscot Mountain Farm Tea House and flesh out the story of its creation and function in turn of the last century Framingham, Massachussetts' life. I believed in and promoted for many years the Rhead landscape vase from his period in Santa Barbara. I bought and sold it twice before it was resold and found its current home in what promises to be one of America's most important museums dedicated to the American Arts and Crafts. I expected to live with Charles Greene's cabinet for the rest of my days. I thought it was the most beautiful thing I have ever had the privilege to call my own for a time. The story around it is remarkable and personally so meaningful to me that I will have to write something special about it sometime in the future. It deserves a chapter all its own...

It is perhaps ironic to say that my complex relationships with objects are due in some part to the many rocky relationships I have had with other people. I have always said that people can be treacherous. A friend is suddenly an enemy or stranger, or a meaningful connection becomes casual and no longer meaningful or as important as it used to be. People's relationships often change radically when circumstances change. Such is life. That has always caused me deep consternation. I work hard to remain constant. And I wrestle to know what my part in the equation has been... A teacup is constant. It will always be a teacup; a tile, a tile. And you can count on a chair or a bookcase in a way which is permanent unless disaster strikes. Maybe it is that constancy, that certainty we have in regard to things which when lived with become familiar to us, which draws us to gather in the first place. We can have confidence in these things to remain "true" in a world which is essentially unknowable and ever-changing... And so I have given my fidelity in a major way to a life of dealing in the exchange of things of virtue and beauty. In return for that commitment to steward them well, I have enjoyed a satisfying and meaningful career. I have also learned a great deal about human nature in the process. When you deal in the world of the decorative arts, the motives of the people you meet run the gamut of human nature -from those with a desire to commune with beauty, or others who are deeply devoted to preserving decorative art history for future generations, to those who are consumed by insecurity and shop to avoid facing the basic emptiness of their lives, or those filled with desire to own motivated by a need for symbols of prestige, wealth, and power. Oh the stories dealers could tell, myself included...But not right now. I'll end this section by stating that regardless of the sometimes transitory connections of human beings, I do have a very healthy number of dear friends whose friendships have lasted through the years as well as many meaningful, long-standing professional relationships.

But back to right now and my essay which is all about the function of things made for utilitarian purposes- objects created to serve the daily uses of humans. And in short order, it is mostly all about milk and the metal containers which traditionally held the precious white liquid while it was in transit to its consumers. The art of working in metal is one of the oldest arts of all. For thousands of years man's crafting in metal has served to fabricate objects which hold our drink and cook our food, help us farm and harness our animals. Work in metal has created our complex tools and machinery, swords and guns and other weapons of war, plowshares and tractors, automobiles and planes and architecture which houses us, has created our workplaces and civic buildings and has generally and specifically lifted civilization up from the stone age. Skilled working in metal has also led to high decorative art and to personal adornments in the form of jewelry, a symbol of status initially for the rich and beautiful among us which then soon became personal decoration available to almost everyone. From Cartier, Tiffany and Lalique, Patek Phillipe watches, Bulgari and Harry Winston brooches and necklaces, to Joan Rivers knockoffs, Swarovsky crystal almost-everything, and nose, eyebrow, ear, and belly piercings for the younger, wilder, and/or more avant garde among us. Studs in foreheads. Yikes! I thought rivets were only for skyscrapers and van Erp lamps... What do I know? Oh yes, Frankenstein's neck, but those were bolts... again I digress...

The precious metals, gold and silver, were worked for artful intent. So too was bronze and brass; even iron. The base metals and alloys, copper, and pewter, tin and nickel silver were used in utilitarian and decorative wares and steel and aluminum too became the life blood of construction, machinery, and architecture.

It is perhaps ironic to say that my complex relationships with objects are due in some part to the many rocky relationships I have had with other people. I have always said that people can be treacherous. A friend is suddenly an enemy or stranger, or a meaningful connection becomes casual and no longer meaningful or as important as it used to be. People's relationships often change radically when circumstances change. Such is life. That has always caused me deep consternation. I work hard to remain constant. And I wrestle to know what my part in the equation has been... A teacup is constant. It will always be a teacup; a tile, a tile. And you can count on a chair or a bookcase in a way which is permanent unless disaster strikes. Maybe it is that constancy, that certainty we have in regard to things which when lived with become familiar to us, which draws us to gather in the first place. We can have confidence in these things to remain "true" in a world which is essentially unknowable and ever-changing... And so I have given my fidelity in a major way to a life of dealing in the exchange of things of virtue and beauty. In return for that commitment to steward them well, I have enjoyed a satisfying and meaningful career. I have also learned a great deal about human nature in the process. When you deal in the world of the decorative arts, the motives of the people you meet run the gamut of human nature -from those with a desire to commune with beauty, or others who are deeply devoted to preserving decorative art history for future generations, to those who are consumed by insecurity and shop to avoid facing the basic emptiness of their lives, or those filled with desire to own motivated by a need for symbols of prestige, wealth, and power. Oh the stories dealers could tell, myself included...But not right now. I'll end this section by stating that regardless of the sometimes transitory connections of human beings, I do have a very healthy number of dear friends whose friendships have lasted through the years as well as many meaningful, long-standing professional relationships.

But back to right now and my essay which is all about the function of things made for utilitarian purposes- objects created to serve the daily uses of humans. And in short order, it is mostly all about milk and the metal containers which traditionally held the precious white liquid while it was in transit to its consumers. The art of working in metal is one of the oldest arts of all. For thousands of years man's crafting in metal has served to fabricate objects which hold our drink and cook our food, help us farm and harness our animals. Work in metal has created our complex tools and machinery, swords and guns and other weapons of war, plowshares and tractors, automobiles and planes and architecture which houses us, has created our workplaces and civic buildings and has generally and specifically lifted civilization up from the stone age. Skilled working in metal has also led to high decorative art and to personal adornments in the form of jewelry, a symbol of status initially for the rich and beautiful among us which then soon became personal decoration available to almost everyone. From Cartier, Tiffany and Lalique, Patek Phillipe watches, Bulgari and Harry Winston brooches and necklaces, to Joan Rivers knockoffs, Swarovsky crystal almost-everything, and nose, eyebrow, ear, and belly piercings for the younger, wilder, and/or more avant garde among us. Studs in foreheads. Yikes! I thought rivets were only for skyscrapers and van Erp lamps... What do I know? Oh yes, Frankenstein's neck, but those were bolts... again I digress...

The precious metals, gold and silver, were worked for artful intent. So too was bronze and brass; even iron. The base metals and alloys, copper, and pewter, tin and nickel silver were used in utilitarian and decorative wares and steel and aluminum too became the life blood of construction, machinery, and architecture.

How did metal come to play a role in servicing mankind's consumption of milk which people have been drinking for thousands of years? First let me share a link to a site which gives an extensive history of the origins of the domestic cow, from early evidence 8000 BC, to 4000 BC of cows having been milked in Great Britain, their role in ancient Sumerian civilization, 3000 BC, the domesticated cow in ancient Egyptian civilization 3100 BC, 2000 BC when it appears in Vedic Northern India, 1700-63 BC where milk is referenced in the earliest Hebrew scriptures, the 1500's and 1600's when the first cattle in the Americas is brought to Vera Cruz, Mexico and the first cattle are brought to New England's Plymouth Colony, 1679-1776 when cattle are introduced by a jesuit priest to the Spanish California missions. Then follows more on milk maids and the compulsory smallpox vaccine in the early 1800's, information on milk production and distillery dairies in the United States, and the process of pasteurization developed 1822-1895 by Louis Pasteur. A telling moment occurs in 1884 when the first glass milk bottles are patented as a result of Dr. Henry Thatcher seeing a milkman make deliveries from an open bucket in which a child's filthy rag doll had fallen by accident. This is a fascinating and informative read which opened my eyes to the history of milk and the nineteenth and twentieth century phenomenon of the milkman and his importance in our culture. That importance has become a thing of the past. I highly recommend this read: milk.procon.org/view.timeline.php?timelineID=000018

Dutch Dog Cart – Morning Milk Delivery in Holland – 1920s Magazine Photo

Dutch Dog Cart – Morning Milk Delivery in Holland – 1920s Magazine Photo

This from B.G. McClure is worth citing as well: "Over two hundred years ago the New England Milk and Cream Dairy traveled only a short distance from the cow to the table. In the hundred years between 1860 and 1960, people moved away from farms and cows, and dairying changed from women’s work at home into a mechanized industry. A delivery person — the milkman — brought dairy products to villages, towns, and cities. At first, milk route men, and occasionally women, came in wagons with milk cans and dippers. Later, the wagons were replaced by fleets of trucks rattling with glass bottles. Without milkmen, generations of families in cities and towns would not have had fresh milk in their coffee, cream on their cereal, or pudding for dessert. Infants would not have had cows’ milk to fill their bottles.

In the same time period, dairying and the milk delivery system had to adapt to change. New processes and government regulation made commercial milk from far away dairies safe to drink, and science and mass advertising persuaded homemakers of milk’s nutritional value. By the 1960s, social, economic, and industrial changes caused milk delivery to shift to the self-service supermarket, and platoons of home delivery milkmen said goodbye..." http://bgmcclure.com/Historical/Milkman.htm

In the same time period, dairying and the milk delivery system had to adapt to change. New processes and government regulation made commercial milk from far away dairies safe to drink, and science and mass advertising persuaded homemakers of milk’s nutritional value. By the 1960s, social, economic, and industrial changes caused milk delivery to shift to the self-service supermarket, and platoons of home delivery milkmen said goodbye..." http://bgmcclure.com/Historical/Milkman.htm

In the same time period, dairying and the milk delivery system had to adapt to change. New processes and government regulation made commercial milk from far away dairies safe to drink, and science and mass advertising persuaded homemakers of milk’s nutritional value. By the 1960s, social, economic, and industrial changes caused milk delivery to shift to the self-service supermarket, and platoons of home delivery milkmen said goodbye..." http://bgmcclure.com/Historical/Milkman.htm

International Harvester McCormick-Deering 3-S Cream Separator with Female Model, 1939. (MM 115002)

Source: Museum Victoria

International Harvester McCormick-Deering 3-S Cream Separator with Female Model, 1939. (MM 115002)

Source: Museum Victoria

Next some further information on the history of milk can farming by Ashley Leonard, eHow Contributor:

"Milk cans were used in the U.S. dairy farming system in the beginning of the 19th century. Dairy farmers stored and transported the milk in these cans to customers in town. Even though milk cans were widely used and the only method of carrying milk at the time, it also impacted dairy farming negatively. In some cases, the milk cans were not cleaned perfectly and the method of transferring the milk to the customer proved to be ineffective and cumbersome...Dairy farmers had a particular way of milking cows during the 19th century. Farmers would milk the cows and the milk would be administered into the pail underneath the udder. The milk was then heated to kill off any bacteria that lived in the liquid. Before pasteurization, this was the best way to get rid of bacteria, but it wasn't always effective. The milk was then stored and cooled in the milk can...The milk was transported within the milk cans by either the farmer or a delivery man. Customers would go where the farmer delivered it so they could get their share. They were required to have a jar or a pail so the farmer could pour milk from the can into that particular container for the customer. This method of transporting and distributing the milk was not ideal because, in most cases, the milk cans were carelessly washed and individuals who were late in getting their milk would get a lower quality of milk. Individuals who came for their milk earlier in the day would get a higher quality of cream, whereas people later in the day would get a lower quality because of the separation...Despite its uses in storing and transporting milk, milk cans had a few faults. Milk cans lacked insulation, so on warm days the milk would start to sour in the can. There wasn't an adequate covering for the milk cans. Plug covers and vegetable parchment were used to cover the can but these options were rather expensive. Milk cans were quite large, with the 10-gallon can being the most popular." Read more : http://www.ehow.com/info_8689908_history-milk-can-farming.html

"Milk cans were used in the U.S. dairy farming system in the beginning of the 19th century. Dairy farmers stored and transported the milk in these cans to customers in town. Even though milk cans were widely used and the only method of carrying milk at the time, it also impacted dairy farming negatively. In some cases, the milk cans were not cleaned perfectly and the method of transferring the milk to the customer proved to be ineffective and cumbersome...Dairy farmers had a particular way of milking cows during the 19th century. Farmers would milk the cows and the milk would be administered into the pail underneath the udder. The milk was then heated to kill off any bacteria that lived in the liquid. Before pasteurization, this was the best way to get rid of bacteria, but it wasn't always effective. The milk was then stored and cooled in the milk can...The milk was transported within the milk cans by either the farmer or a delivery man. Customers would go where the farmer delivered it so they could get their share. They were required to have a jar or a pail so the farmer could pour milk from the can into that particular container for the customer. This method of transporting and distributing the milk was not ideal because, in most cases, the milk cans were carelessly washed and individuals who were late in getting their milk would get a lower quality of milk. Individuals who came for their milk earlier in the day would get a higher quality of cream, whereas people later in the day would get a lower quality because of the separation...Despite its uses in storing and transporting milk, milk cans had a few faults. Milk cans lacked insulation, so on warm days the milk would start to sour in the can. There wasn't an adequate covering for the milk cans. Plug covers and vegetable parchment were used to cover the can but these options were rather expensive. Milk cans were quite large, with the 10-gallon can being the most popular." Read more : http://www.ehow.com/info_8689908_history-milk-can-farming.html

Holstein Friesians are a breed of cattle known today as the world's highest-production dairy animals. Wikipedia

Holstein Friesians are a breed of cattle known today as the world's highest-production dairy animals. Wikipedia

And here, from Wikipedia, a bit of history on the all-important cows which produced our milk: "Holstein Friesians (often shortened as Friesians in Europe, and Holsteins in North America) are a breed of cattle known today as the world's highest-production dairy animals. Originating in Europe, Friesians were bred in what is now the Netherlands and more specifically in the two northern provinces of North Holland and Friesland, and northern Germany, more specifically what is now Schleswig-Holstein Germany. The animals were the regional cattle of the Frisians and the Saxons. The Dutch breeders bred and oversaw the development of the breed with the goal of obtaining animals that could best use grass, the area's most abundant resource. Over the centuries, the result was a high-producing, black-and-white dairy cow. It is black and white due to artificial selection by the breeders...

With the growth of the New World, markets began to develop for milk in North America and South America, and dairy breeders turned to the Netherlands for their livestock. After about 8,800 Friesians (black pied Germans) had been imported, disease problems in Europe led to the cessation of exports to markets abroad.[1] CIV, France, a tradition of animal husbandry. Animal husbandry and environment. Civ-viande.org. Retrieved on 2011-11-03...American breeders began to become interested in Holstein-Friesian cattle around the 1830s. Black and white cattle were introduced into the US from 1621 to 1664. The eastern part of New Amsterdam (present day New York) was the Dutch colony of New Netherlands, where many Dutch farmers settled along the Hudson and Mohawk River valleys. They probably brought cattle with them from their native land and crossed them with cattle purchased in the colony. For many years afterwards, the cattle here were called Dutch cattle and were renowned for their milking qualities."

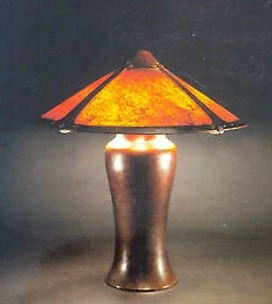

By now you must be thinking "Hasn't he tortured me enough with all this stuff about grass fermented in the bellies of cows? Is it going to take another eight thousand years before we know where he is going with all this?" The answer is "No." What I'm driving toward is a minute away... I've made you travel down this milky road to stress the importance of Holland in helping milk become available to all of us in America. Every Dutch man and woman here is keenly aware of how much we owe Holland for its Holsteins and its heritage of animal husbandry which led to the proliferation of the breed most responsible for dairy production here. And all of this serves to set up a bit of dialogue about the van Erp studio and the style of lamp which has come to be known as the Milkcan lamp. That lamp form is one of the rarest and most desired in the van Erp repertoire and is pictured on the left in the trio of pictures later on in this essay. I have never had the opportunity to buy or sell one although I have had many wonderful examples of the studio's lamps. Perhaps the most wonderful one I have ever owned looked like this one:

The handled vase which captured my imagination with the damage which encircled the piece pictured.

The handled vase which captured my imagination with the damage which encircled the piece pictured.

Here is a pertinent tale about copper and milkcans. In the mid 1990's a number of men and women in the East Bay and some of us here in San Francisco joined together to put on a lecture series for a number of years at the Swedenborgian Church here in the city. My talk was on the development of my aesthetic and people seemed to enjoy it. And I had fun thinking about the topic and developing the substance of what I wanted to share. Many in the group were friends with the pastor, Reverend Jim Lawrence, and all admired the church, its deep roots in the Arts and Crafts movement and its pastor and parish's desire to honor that heritage and bring it forward into the twentieth century. There was abiding intent to restore and refurbish the church and its attendant buildings. I was fortunate enough to locate the missing eightieth Forbes chair and see to it that it was returned to the church. Some women had come into my shop and said they had deceased relatives who had been members of the church at the turn of the century and that they had a number of objects of theirs they wanted to sell. Most were Victorian pieces but among them was the chair which I bought and passed along at a modest profit back to the church which was its place of origin. Very satisfying all the way round. I then became involved in the painting of the kindergarten room which I did in a modified English crafts style in tribute to the work of Walter Crane and Bailey Scott-doves on the trunk and built in wardrobes and a simple landscape across the fireplace hearth. It worked and the children liked it. There were limited funds to decorate the building in which receptions were held after weddings and so I suggested some furniture from my shop might be in keeping. I had also seen a battered piece of copper in a room with a hearth, a handled vase. For some reason it caught my eye. I think : One. I saw it as "wounded". Two: I was intrigued by its form, that handle and spouts, and Three: I wanted to save it.

The "milkcan" today.

The "milkcan" today.

The church hadn't a lot of money to spend on restoration so I struck a deal with them and "rescued" the piece in exchange for a number of pieces of signed Arts and Crafts furniture including a spindled cube settle and chair by Brooks and a three drawer library table by L. & J.G. Stickley which made the main reception room warm, inviting, and serviceable. Fair market value at the time was considerable. The vase was a mess as far as they were concerned and not worth much at all, especially all banged up as it was. I think they thought I was crazy. And I thought I was more than a little nuts too. But when a thing speaks to me, dollars seem unimportant and I knew it would be a good deal for the church as well. So we made a trade and I went home with this mysterious piece of unmarked, badly dented copper. I was, I guess, okay with that. Over a period of years, I worked on it repeatedly and did my best to bring it back to a second life-copper is a forgiving metal. I have loved living with it ever since. I had no idea who had made it. It was just intriguing in the extreme. I wanted to look at it, fix it if I could, and think about cloudy feelings it brought up in me. Oh, what was it trying to tell me?

The classic van Erp milkcan lamp A copper milkcan from Scotland A double handled milkcan from the southern United States.

It's been about twenty years ago now. After all that time, I have come to believe that the piece is the work of August Tiesselinck, the foreman of the van Erp studio. He had a workshop on Fillmore in the late teens and early twenties. A few years ago a magnificent chandelier came up at auction in the East. In my opinion it had all the earmarks of Tiesselinck's hand too. It had been in the house adjacent to the Swedenborgian Church. I thought the coincidence of two pieces of fine copper work near one another went a long way toward supporting my attribution. There were no records associated with the Church's having acquired the piece. No one there had any record of how it came to be there either although it was allowed that it had been there for quite some time. Could it be that some eighty years earlier a parishioner had visited August's shop nearby and bought the piece to donate as decoration for the "living room" in the church's reception hall? Had it come as a gift from August himself? Or was it purchased directly by the church? I still wonder and have no answer. Nonetheless, initially and repeatedly, when I look at this receptacle a light bulb incandesces in my brain. Here is this form substantiating the fact that what has come to be known as the "milk can" lamp from the van Erp studio certainly has more than one variation. This is clearly a milk can. The double spout and handle suggest that when it was filled it was heavy and that it was worthwhile to be able to conveniently pour from whichever end might be closer to the receptacle receiving its contents. So I offer here this little overview to substantiate the fact that here is a new example of the milk can. I show it along with another variant of the form from Scotland which has the same double spouted, handled elements but little of the sweeping grace of the form which says "van Erp" in its every aspect. Also shown is another two handled milk can which came from the deep South of the United States. This third variation of the milk can emphasizes the need to utilize two handles in the place of two spouts. These containers were very heavy when they were filled. One handle at the top allowed control when the container was full; the other, allowed similar control when the container was nearing the bottom of its contents. Ingenious design where form completely defines function. It turns out that I didn't know it but I have been collecting van Erp milk cans all this time! While I do not have an example of the standard, I have numerous examples of the second form to show and share... Clearly, when it came to the creation of some of their classic lighting designs in America, Dirk and August looked to their heritage as proud Dutch men, inspired by Holland's conventional forms of utilitarian copperware used in the transporting of milk from farms to the neighboring households. Interesting, right? And so beautiful to behold...

Isak Lindenauer September 20, 2014

Isak Lindenauer September 20, 2014

Some examples of the milkcan form in copper by van Erp.

Some examples of the milkcan form in copper by van Erp.

Postscript

I could explain my having inundated you with a thousand and one milky facts as my attempt to increase your focus on what was in the twentieth century a ubiquitous sense of the importance of milk in our daily lives. That importance has disappeared to a great degree. Things and their uses come and go as time goes by. Take cereal as an example, Wheaties and Rice Crispies became granola, and now "gluten-free" is the thing, and the cereal industry is off by twenty-five percent as people once again, have begun to look at breakfast differently. Who thinks of aluminum these days? We certainly likely have a roll of it in one of our kitchen's drawers, but it is not on the tip of our tongues even though it "is the most common metal in the world, and the third most common element.. It is durable and lightweight, and is a very important metal for making planes out of...Aluminium is used for building (particularly frames for doors and windows) and vehicle construction, ... masts on ships,...and lots of household utensils and appliances."

http://photographicdictionary.com/metals

Those of us who grew up in the fifties and remember television's Omnibus and Alastair Duncan, will have a different sense of the word "aluminum" when I ask this question. What that suggests to me is that in an almost Jungian sense, things and their uses and prevalence in society give rise to ideas and concepts which lead to the creation of new things. It's as though without a certain confluence of factors, van Erp's milkcan lamps might not have been created when they were. They came out of the world around them, naturally evolved, if you will. Today the world is a very different place. I imagine that without those who are involved in interior design or in the crafting of reproductions both of whom look to the past for inspiration these forms would not continue to take hold, find expression in design vocabulary, or come into being again in quite the same way.

Copyright © 2014-2021, 2020-2025

Isak Lindenauer

I could explain my having inundated you with a thousand and one milky facts as my attempt to increase your focus on what was in the twentieth century a ubiquitous sense of the importance of milk in our daily lives. That importance has disappeared to a great degree. Things and their uses come and go as time goes by. Take cereal as an example, Wheaties and Rice Crispies became granola, and now "gluten-free" is the thing, and the cereal industry is off by twenty-five percent as people once again, have begun to look at breakfast differently. Who thinks of aluminum these days? We certainly likely have a roll of it in one of our kitchen's drawers, but it is not on the tip of our tongues even though it "is the most common metal in the world, and the third most common element.. It is durable and lightweight, and is a very important metal for making planes out of...Aluminium is used for building (particularly frames for doors and windows) and vehicle construction, ... masts on ships,...and lots of household utensils and appliances."

http://photographicdictionary.com/metals

Those of us who grew up in the fifties and remember television's Omnibus and Alastair Duncan, will have a different sense of the word "aluminum" when I ask this question. What that suggests to me is that in an almost Jungian sense, things and their uses and prevalence in society give rise to ideas and concepts which lead to the creation of new things. It's as though without a certain confluence of factors, van Erp's milkcan lamps might not have been created when they were. They came out of the world around them, naturally evolved, if you will. Today the world is a very different place. I imagine that without those who are involved in interior design or in the crafting of reproductions both of whom look to the past for inspiration these forms would not continue to take hold, find expression in design vocabulary, or come into being again in quite the same way.

Copyright © 2014-2021, 2020-2025

Isak Lindenauer