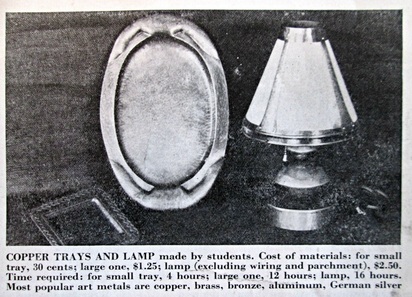

First grouping of Bay Area copper.

First grouping of Bay Area copper.

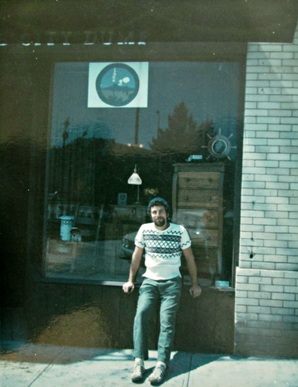

Me in front of The City Dump, 1973

Me in front of The City Dump, 1973

Essay Number Five June 27, 2014

SOME THOUGHTS ON BAY AREA COPPER

I opened my first antique shop at Ashby on Adeline in 1973 when I was a young lad of twenty-seven years. I had been collecting pieces of Arts and Crafts for some time by then without knowing what the objects were. I just liked them. As a Freshman English student, I had walked around Berkeley looking at Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan architecture not knowing who had designed the buildings but had been strongly drawn to them too. Who got to live in houses with river rock and shingles, inviting inglenooks and fireplaces you could see from the outside front window, with wysteria hanging over the eaves and bamboo in the back yard? What was this place,The First Church of Christ Scientist, I looked down on from my eighth floor dorm window? The questions propelled me to look into Maybeck and Morgan's work and I began to read about the period.

Robert Judson Clark had published his book written as a catalog for the seminal exhibition at Princeton in 1972 which was soon followed by Eudorah Moore's book in 1974 called California Design written to accompany the ensuing exhibition of California Arts and Crafts in Pasadena. Soon, I had seen and read them both with intense interest and recognized that many of the things I had collected for my home were actually signed pieces: Stickley and Limbert, Newcomb and Rookwood. That was the start of it all. Flash forward a few years and find that life had led me down a path different from my earlier intent to teach English and try my hand at writing. By 1973, I was selling a general line of antiques in a shop of my own. But that all changed by the end of the first year....There were only a few dealers of Arts and Crafts on the West Coast at that time and I realized it was what I wanted to show and collect. I began to specialize. Forty-one years have passed since I began that journey. I have remained a seller of this style.

My first teacher, Ken Dane, used to regularly invite me to his family's house in Albany. I would sit at their dining table afternoons or evenings, asked to stop by for dinner or coffee and pastry with his wife and daughters. Afterward, Ken would bring out examples of American Art Pottery, place them on the table, and explain the background of each firm or individual maker. In that way, I came to appreciate more deeply the pieces I had been drawn to on my own when hunting at garage sales, flea markets, antiques shops and shows

SOME THOUGHTS ON BAY AREA COPPER

I opened my first antique shop at Ashby on Adeline in 1973 when I was a young lad of twenty-seven years. I had been collecting pieces of Arts and Crafts for some time by then without knowing what the objects were. I just liked them. As a Freshman English student, I had walked around Berkeley looking at Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan architecture not knowing who had designed the buildings but had been strongly drawn to them too. Who got to live in houses with river rock and shingles, inviting inglenooks and fireplaces you could see from the outside front window, with wysteria hanging over the eaves and bamboo in the back yard? What was this place,The First Church of Christ Scientist, I looked down on from my eighth floor dorm window? The questions propelled me to look into Maybeck and Morgan's work and I began to read about the period.

Robert Judson Clark had published his book written as a catalog for the seminal exhibition at Princeton in 1972 which was soon followed by Eudorah Moore's book in 1974 called California Design written to accompany the ensuing exhibition of California Arts and Crafts in Pasadena. Soon, I had seen and read them both with intense interest and recognized that many of the things I had collected for my home were actually signed pieces: Stickley and Limbert, Newcomb and Rookwood. That was the start of it all. Flash forward a few years and find that life had led me down a path different from my earlier intent to teach English and try my hand at writing. By 1973, I was selling a general line of antiques in a shop of my own. But that all changed by the end of the first year....There were only a few dealers of Arts and Crafts on the West Coast at that time and I realized it was what I wanted to show and collect. I began to specialize. Forty-one years have passed since I began that journey. I have remained a seller of this style.

My first teacher, Ken Dane, used to regularly invite me to his family's house in Albany. I would sit at their dining table afternoons or evenings, asked to stop by for dinner or coffee and pastry with his wife and daughters. Afterward, Ken would bring out examples of American Art Pottery, place them on the table, and explain the background of each firm or individual maker. In that way, I came to appreciate more deeply the pieces I had been drawn to on my own when hunting at garage sales, flea markets, antiques shops and shows

The first piece of pottery I ever bought.

Newcomb college. New Orleans.

Cynthia Littlejohn, 1918

The first piece of pottery I ever bought.

Newcomb college. New Orleans.

Cynthia Littlejohn, 1918

My first pottery purchase was at the Alameda Flea- a piece of Newcomb with a hairline. It was seven dollars. I couldn't walk away from it try as I might. As I left the flea market, I still couldn't believe that I had bought it. I had never spent that much on a piece of pottery before. And it had a hairline! But it called to me like the very sirens called to Odysseus and his crew. I lived with it for two or three years before finding out from the exhibition catalogs that it was very collectible ceramic from New Orleans. I have it to this day... Ken also showed me the work of the Dirk van Erp studio. I had seen pictures of the lamps and metalware in the show catalogs, but seeing a piece in person was very different.

Classic Dirk van Erp boudoir lamp. 13" high.

Classic Dirk van Erp boudoir lamp. 13" high.

I wanted a van Erp lamp like a little boy wants a red wagon for Christmas. In those days, the work was held in extremely high regard and the world of antiques was very different from the one of today. To begin with, there were no reproductions of Arts and Crafts objects of any kind. Second, when a serious collector chanced upon a van Erp lamp in a shop for sale, he also encountered high protocol. I'll just say that if you wanted to know the price, you had better be intent on purchasing it. It was not something to be casually interested in. And dealers were quick to let you know that. (Sometimes these days someone will come into my shop and point to a van Erp lamp or two and ask me "How much do these lamps run?" I say "These lamps don't run. They're valuable and collectible. Some cost tens of thousands of dollars." I know some people are put off but it gives me great satisfaction to invoke that old protocol.) If an antique dealer thought you were shopping his objects to learn prices, you were not given an answer. Instead you were ushered out the front door by whatever means was called for- a sharp word or a look of great disdain. Collecting was a much more formal proposition back then. One afternoon, I found the first van Erp lamp I had ever seen for sale. It was in a shop off Polk street on the other side of Stockton. It was a D'Arcy Gaw lamp and I dared to ask, because as I have previously said, I was dead set on having one of my own. So I mustered up my courage and asked the question. I made it very clear that I was serious about a possible purchase and was told that it was seven hundred and fifty dollars. Well, my rent at that time was about one hundred and thirty-five dollars and I had practically nothing in the way of funds. Everything I made went right back into building the shop inventory. So it was entirely out of the question. Undaunted by reality, I told them I would try to put the money together and would get back to them in a few days. I mentioned it to Ken who said it was too much money. I went back to look at it again to see if I could talk the shopkeeper into letting me pay for it over time but it had quickly been snapped up by someone else.

I was so disappointed. Ken promised he would let me know when he had another for sale and called one day to tell me he had one for me. It was a boudoir lamp. (Today, contemporary crafters tend to call them "bean pots". Van Erp would roll over in his grave to hear them called that!)

I went right over to see it. It was four hundred and fifty dollars and I had to have it. I arranged to pay Ken one hundred dollars down and the rest over the following three months and the lamp became mine. Who cared where the rent money would come from? I would have that lamp come what may... And did.

To my way of thinking, the boudoir lamp is one of van Erp's most perfected designs, useful in places where most other lamps are too large to work well. Why do I say that ? Well, as an example of its power and beauty, I'll add this: It was the sort of lamp held on to by many-among others, many an older woman, who having lost her husband, had moved out of their large home into a smaller apartment and then on to a rest or retirement home. It was inevitably the one thing from earlier days along with family photographs or other cherished mementos that she took with her and it remained by her bedside til her last day... I know because more than once family members have related that progression to me after a lamp had been inherited and was then offered to me for sale. Other dealers I knew recounted similar stories. To me it was a poignant, repeated testament of affection. This one which Ken had offered was the only van Erp within a range I could commit to so I could start my own stewardship.

I was so disappointed. Ken promised he would let me know when he had another for sale and called one day to tell me he had one for me. It was a boudoir lamp. (Today, contemporary crafters tend to call them "bean pots". Van Erp would roll over in his grave to hear them called that!)

I went right over to see it. It was four hundred and fifty dollars and I had to have it. I arranged to pay Ken one hundred dollars down and the rest over the following three months and the lamp became mine. Who cared where the rent money would come from? I would have that lamp come what may... And did.

To my way of thinking, the boudoir lamp is one of van Erp's most perfected designs, useful in places where most other lamps are too large to work well. Why do I say that ? Well, as an example of its power and beauty, I'll add this: It was the sort of lamp held on to by many-among others, many an older woman, who having lost her husband, had moved out of their large home into a smaller apartment and then on to a rest or retirement home. It was inevitably the one thing from earlier days along with family photographs or other cherished mementos that she took with her and it remained by her bedside til her last day... I know because more than once family members have related that progression to me after a lamp had been inherited and was then offered to me for sale. Other dealers I knew recounted similar stories. To me it was a poignant, repeated testament of affection. This one which Ken had offered was the only van Erp within a range I could commit to so I could start my own stewardship.

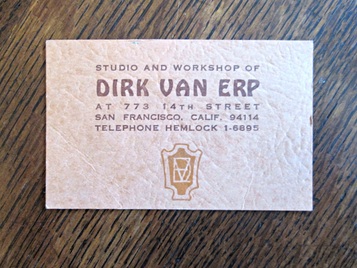

The business card of the Dirk van Erp studio, circa 1974

The business card of the Dirk van Erp studio, circa 1974

That's pretty much how my passion for van Erp metal began. It has never stopped. Soon I was making pilgrimages to the workshop on 14th Street. William was in his middle seventies then and he and Larry Roberts, the last worker to work at the shop with him, would sit in the back at the long workbench and tell me stories as they worked on pieces. I sat there with pen and paper in hand, wide-eyed, writing oral histories. Surrounded by the tools and the work in progress, I was thrilled beyond belief to be able to be there and talk to both of them. William's legs were bad at that time and when I would come over with some work for them to do for me, I'd bring him epsom salts, and sit with them, watch them work and ask them question after question. I will always be grateful to have had those brief years in their company. They both were gentle men who couldn't have been kinder to me. William said one thing to me I feel is imperative to pass on. He told me that nothing, absolutely nothing, ever left the workshop without being signed with the windmill hallmark. Van Erp senior was so proprietary in regard to the copper which came out of the workshop, he was intent on its being identifiable as his work.

Truthfully, in later years, I came to realize his statement was not completely accurate. There are some pieces, particularly some pieces in desk sets or fireplace sets, which were not signed. I believe that is because either the shape was not conducive to having a mark hammered into it or the crafters felt that as long as the set was being sold together, a number of key marked pieces in the set was sufficient. Because van Erp copper soon became so sought-after and commanded so much money, I never contradicted what William told me back then. In fact, because some dealers had begun to pass off unsigned pieces as the work of the van Erp studio, which clearly weren't on the basis of poor craftsmanship alone, I held firm to William's dictum in an attempt to protect the level and quality of work new collectors and old would come to recognize and value as van Erp. I still hold to that practice, today more than ever. This last year or two, more shoddy, unsigned copperwork has been passed off to unsuspecting collectors as being the unsigned work of the van Erp studio than I have ever seen in the past. And many were sold for many thousands of dollars. It is very disappointing to me to see the firm's reputation muddied in this way by profiteers. New collectors rarely have any real reference other than by looking through old catalogs of exhibitions and by listening to people whom they believe to be reputable and knowledgeable. Those of us who have the advantage of years of experience looking at examples of this copper, have a responsibility to tell the truth. I have worked for forty years to promote the studio's work and have represented it with pride as being some of the most consistent and beautiful copper craft from the American Arts and Crafts era. And that consistency and beauty continued to be the case until the shop closed after William's death in 1976. Right or wrong, I have only called "van Erp" those pieces which had the windmill hallmark in one of its various permutations. That seemed the best thing to do. Or if not the best thing to do, certainly the lesser of two evils by far...

Truthfully, in later years, I came to realize his statement was not completely accurate. There are some pieces, particularly some pieces in desk sets or fireplace sets, which were not signed. I believe that is because either the shape was not conducive to having a mark hammered into it or the crafters felt that as long as the set was being sold together, a number of key marked pieces in the set was sufficient. Because van Erp copper soon became so sought-after and commanded so much money, I never contradicted what William told me back then. In fact, because some dealers had begun to pass off unsigned pieces as the work of the van Erp studio, which clearly weren't on the basis of poor craftsmanship alone, I held firm to William's dictum in an attempt to protect the level and quality of work new collectors and old would come to recognize and value as van Erp. I still hold to that practice, today more than ever. This last year or two, more shoddy, unsigned copperwork has been passed off to unsuspecting collectors as being the unsigned work of the van Erp studio than I have ever seen in the past. And many were sold for many thousands of dollars. It is very disappointing to me to see the firm's reputation muddied in this way by profiteers. New collectors rarely have any real reference other than by looking through old catalogs of exhibitions and by listening to people whom they believe to be reputable and knowledgeable. Those of us who have the advantage of years of experience looking at examples of this copper, have a responsibility to tell the truth. I have worked for forty years to promote the studio's work and have represented it with pride as being some of the most consistent and beautiful copper craft from the American Arts and Crafts era. And that consistency and beauty continued to be the case until the shop closed after William's death in 1976. Right or wrong, I have only called "van Erp" those pieces which had the windmill hallmark in one of its various permutations. That seemed the best thing to do. Or if not the best thing to do, certainly the lesser of two evils by far...

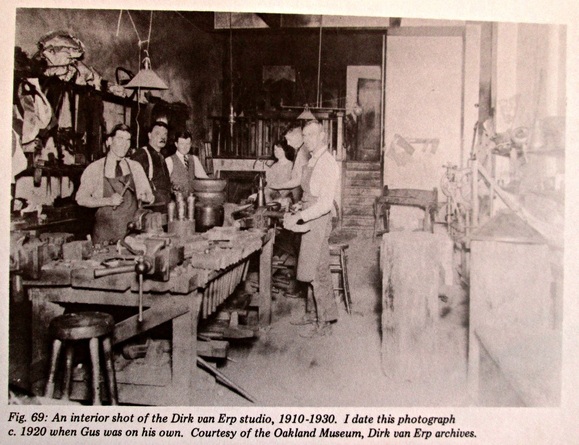

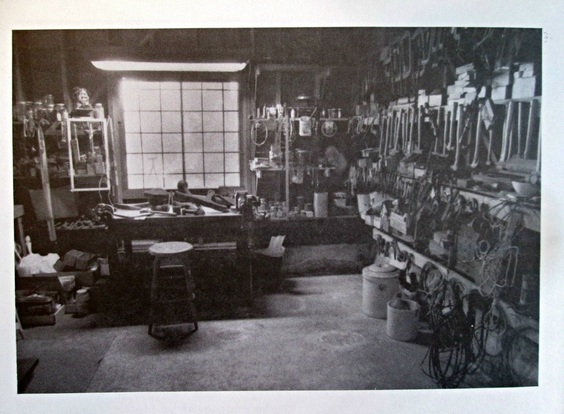

The basement work shop of August Tiesselinck circa 1988. Courtesy of Jean Tiesselinck

The basement work shop of August Tiesselinck circa 1988. Courtesy of Jean Tiesselinck

I'd like to share what I consider to be a more appropriate way to speak about the examples of unsigned copper work presumed to come from the Bay Area, especially pieces which have visual references to the many designs from the van Erp studio. There are a number of other possibilities as to who made these pieces and to how they came to be made. First, it must be understood that while the Bay Area was rich in its number of crafters in metal, all of them had a very difficult time earning a living at their chosen craft. Even the shops which were well-known struggled to keep their shops operating, their doors open, and their people employed and earning a decent living. Many of those who worked at the van Erp studio had workshops in the basements of their homes; others, like van Erp's daughter Agatha van Erp, taught classes in her home when she was not working in the shop proper. August Tiesselinck hammered and raised forms in his basement workshop at home to make gifts for friends. In 1919 he had a shop of his own for a brief period, and he worked and crafted copper in another shop in San Francisco and in studios and classrooms where he taught. It has often been said that workers from the van Erp shop moonlit to create outside income and also crafted without using the shop hallmark when they made a gift for a family member or friend. All of these instances offer one very clear explanation for the existence of pieces which have the earmarks of van Erp studio design yet lack the studio's signature. Anyone having made pieces at the studio may have been responsible for unsigned examples which were done outside of the studio at any point in time.

A second explanation rests with a closer look at the career of August Tiesselinck, the foreman of the van Erp studio, its main instructor and one of its chief designers. August, van Erp's nephew, worked at van Erp's for three different periods, leaving and returning, leaving again and coming back, and finally leaving to go out and start a shop of his own. In between those distinct tenures, he was foreman of the Lillian Palmer Shop. And after his third tenure at van Erp's, he entered the San Francisco public school system, acquiescing to the continued request of the Superintendant of Schools, where he then taught metalwork at Mission High for the next thirty years. Mr. Tiesselinck would sign his work in a variety of ways or just as often leave it without any signature at all. He was primarily concerned with making things in metal and teaching. Atypically for a crafter of note, he had little concern for public acclaim or recognition-unlike van Erp who was very concerned with promoting his own name and the work of his studio. In fact, even though at the height of the studio's production there were as many as sixteen men and women forming and raising pieces, there are very few instances where work from the studio is signed with any name other than that of Dirk van Erp's. In all the years I have been collecting and selling the studio's work, I have only seen three or four pieces which have marks other than the van Erp signature on them. William was so influenced by this intent that in later years he still answered to the name "Dirk van Erp" and signed some of his invoices and paperwork with the "Dirk van Erp" signature.

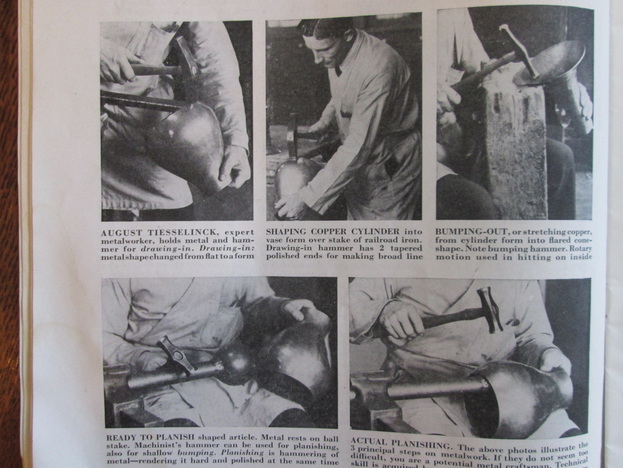

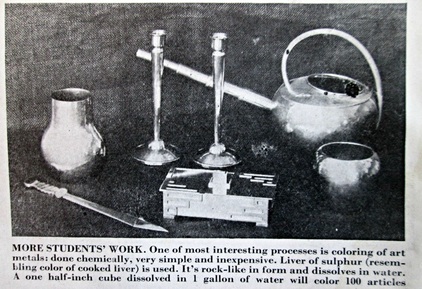

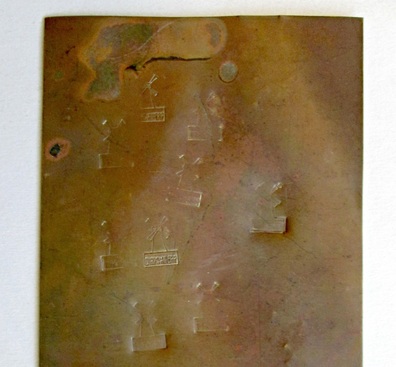

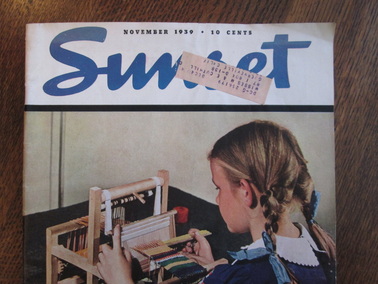

Sunset magazine. November 1939

Sunset magazine. November 1939

Another explanation for the existence of unsigned copper work of great accomplishment and the "look" of van Erp, is the fact that it is the work of professional crafters who studied under Mr.Tiesselinck, or students whom he instructed. This is especially true with the student work which came out of Mission High School. An article in Sunset magazine published in 1939 on Tiesselinck and his students has a number of pictures of their projects which any van Erp afficionado, if asked to identify its maker without the ability to turn it over to find its hallmark, will automatically guess: "van Erp"- and from the classic early period at that! August also gave master classes in metalwork to teachers who came from all over the West Coast to study with him. As such, he is responsible for the dissemination of Old World metal techniques to an entire generation of professional metalsmiths all of whom may have crafted objects in this style.

Over the last ten or fifteen years, I have seen dealers try to capitalize on the fact that Mr. Tiesselinck was so free in regard to signing or not signing his craft. I have done all that was possible to deter that profit motive in others when I thought the work they showed me was without merit. In fact, in all that time, I can honestly say I have seen less than a handful of unsigned pieces which I could attribute with confidence to his hand. It is no easy thing to identify with authority unsigned copper work. There are and were a great many accomplished crafters from all over the country and from outside of America as well. The hammer and the creations which come from its use can be very similar although the tool may have been a different one held in many different hands and in many different eras. I don't take the task of identifying work lightly as I have become associated with the recognition of Mr.Tiesselinck's work and seek to protect his good name as intently as that of van Erp's.

A further complication to the identifying and mis-identifying of van Erp copper comes from the introduction of forgeries which are a relatively new problem but a serious one. When I have seen forgeries with the van Erp hallmark, the pieces have had so little craftsmanship that it was readily apparent the piece was a fake. But not everybody is so conversant with San Francisco copper as some of us are. People have been coming to my shop with increasing frequency asking me to authenticate pieces which have turned out to be fraudulent so I mention it as a warning to collectors. Be sure before you buy...

A further complication to the identifying and mis-identifying of van Erp copper comes from the introduction of forgeries which are a relatively new problem but a serious one. When I have seen forgeries with the van Erp hallmark, the pieces have had so little craftsmanship that it was readily apparent the piece was a fake. But not everybody is so conversant with San Francisco copper as some of us are. People have been coming to my shop with increasing frequency asking me to authenticate pieces which have turned out to be fraudulent so I mention it as a warning to collectors. Be sure before you buy...

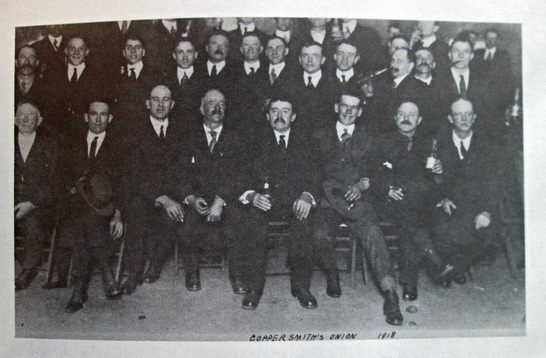

The San Francisco Coppersmith's Union. 1918 Courtesy of Jean Tiesselinck.

( Dirk van Erp, fifth from the left in the second row. August Tiesselinck in the back row, his face not visible in this photo.)

The San Francisco Coppersmith's Union. 1918 Courtesy of Jean Tiesselinck.

( Dirk van Erp, fifth from the left in the second row. August Tiesselinck in the back row, his face not visible in this photo.)

Yet another consideration is the fact that the Coppersmith's Union here in the Bay Area had many accomplished industrial crafters. They had the technical ability to make pieces in the style of van Erp and they were near enough to the work itself which was sold in the studio's salesroom as well as through a number of fine stores locally. It would have been easy for any one of them to examine and copy those pieces. These local smiths constitute one further possibility as to where unsigned pieces may have come from.

These are by no means all the possible explanations for unsigned pieces, but they are notable ones. It is my intent in writing this to reclaim the sanctity, if you will, of the van Erp signature, to protect the quality of the studio's output, and to clarify the currently muddied waters. In conclusion, I would say we would all be better off to call these pieces: Bay Area school copper, van Erp school copper, and/or Tiesselinck school copper. All these possibilities are more likely to be the truth of the origin of so many unsigned pieces rather than to mis-attribute them by referring to them as "unsigned van Erp". It is not worthwhile to say that. It has the potential to do more harm than good. Personally, as I have already stated, I'd rather say there is no unsigned van Erp copper. What will follow this next week to illustrate the above points are examples of signed van Erp Studio work which will be for sale as well as unsigned examples of Bay Area copper work which will also be for sale. The offering will feature a range of examples with commensurate prices in an attempt to reset and redevelop a guide toward more responsible evaluation of pieces of Bay Area copper at this point in time. I hope this tract proves helpful to the interested collecting public.

Copyright © 2014-2021, 2020-2025

Isak Lindenauer

Isak Lindenauer