Essay Number Three: August 27th, 2013

A singular Collaboration:

The Charles Strothoff oak tree lamp

by the studio and workshops of Dirk van Erp and Thomas Gotham

A singular Collaboration:

The Charles Strothoff oak tree lamp

by the studio and workshops of Dirk van Erp and Thomas Gotham

Strothoff hammered copper and crystalline porcelain lamp with oak tree motif

The lamps from the workshop of the Dirk van Erp Studios in San Francisco which were made between 1910 and 1929 are among the finest lamps ever crafted by artisans of this period. The hammering is exemplary; the forms, sublime. Strongly influenced by the classic, meditative forms of ancient Asian vessels-some in metal, others in porcelain, van Erp's designs are wonderful transformations of copper into pure philosophical objects of use and beauty.

The Strothoff lamp is unique among them in a number of ways. Charles Strothoff knew Dirk van Erp. He was born in San Francisco in 1892, raised and went to school here, and ultimately became an architect. He knew of the workshop on Sutter Street and would often stop in and speak with the men. It's my belief that in the early 1920's, Strothoff asked van Erp to make a lamp for him that he would eventually keep in his office, using as its body, a large crystalline vase made by Thomas Gotham who was then working at West Coast Porcelain Manufacturers in Milbrae producing exemplary crystalline forms. It is more likely that the Gotham vase came from someone outside the studio, like Strothoff or a close family member bringing it in with a special request than from within the studio since, to date, no other lamps by van Erp are known to have been crafted utilizing the crystalline work of Gotham's vases. Perhaps Strothoff had seen and admired some of the lamps produced by California Porcelain and Gotham in Milbrae which are similar in so far as the use of a crystalline body is concerned. Regardless of the validity of my conjecture, van Erp did agree to make a copper lamp for Strothoff using the Gotham vase as its beginning form. I imagine that if Strothoff brought the Gotham vase to van Erp, as an architect requesting a highly specific commission he would soon feature in his office, he would have had some input into what the design elements would consist of. If it had not been initiated by Strothoff, it would most certainly have been asked of him by the craftsman. The van Erp Studio was known for personalizing their work through the use of monograms for example, and decorative cut-outs and riveted applications of design motifs like trees, diamonds, bamboo, and poppies; all were popular choices which could be requested by clients as well. The crafters were very responsive to the creative "wants" of their patrons.Through some permutation of the variables above the Strothoff oak tree lamp came to be created. I have owned the lamp for some sixteen or seventeen years and purchased it directly from a relative of Charles Strothoff's and have agreed to respect that person's privacy, although most of the inferences I have made in regard to the creation of the lamp have been drawn from conversations we have had about it over these many years.

The Strothoff lamp is unique among them in a number of ways. Charles Strothoff knew Dirk van Erp. He was born in San Francisco in 1892, raised and went to school here, and ultimately became an architect. He knew of the workshop on Sutter Street and would often stop in and speak with the men. It's my belief that in the early 1920's, Strothoff asked van Erp to make a lamp for him that he would eventually keep in his office, using as its body, a large crystalline vase made by Thomas Gotham who was then working at West Coast Porcelain Manufacturers in Milbrae producing exemplary crystalline forms. It is more likely that the Gotham vase came from someone outside the studio, like Strothoff or a close family member bringing it in with a special request than from within the studio since, to date, no other lamps by van Erp are known to have been crafted utilizing the crystalline work of Gotham's vases. Perhaps Strothoff had seen and admired some of the lamps produced by California Porcelain and Gotham in Milbrae which are similar in so far as the use of a crystalline body is concerned. Regardless of the validity of my conjecture, van Erp did agree to make a copper lamp for Strothoff using the Gotham vase as its beginning form. I imagine that if Strothoff brought the Gotham vase to van Erp, as an architect requesting a highly specific commission he would soon feature in his office, he would have had some input into what the design elements would consist of. If it had not been initiated by Strothoff, it would most certainly have been asked of him by the craftsman. The van Erp Studio was known for personalizing their work through the use of monograms for example, and decorative cut-outs and riveted applications of design motifs like trees, diamonds, bamboo, and poppies; all were popular choices which could be requested by clients as well. The crafters were very responsive to the creative "wants" of their patrons.Through some permutation of the variables above the Strothoff oak tree lamp came to be created. I have owned the lamp for some sixteen or seventeen years and purchased it directly from a relative of Charles Strothoff's and have agreed to respect that person's privacy, although most of the inferences I have made in regard to the creation of the lamp have been drawn from conversations we have had about it over these many years.

Close-up of the oak tree cut out motif at the outer border of the van Erp shade. This cut out motif repeats three times around the shade bottom border at the middle of each of its three panels.

A close-up of the Thomas Gotham crystalline vase which has been crafted into a base for the van Erp lamp. The brown glaze and the many explosive crystals which cover the body of the vase approximate the feeling of hammer marks across the surface of a patinated copper form.

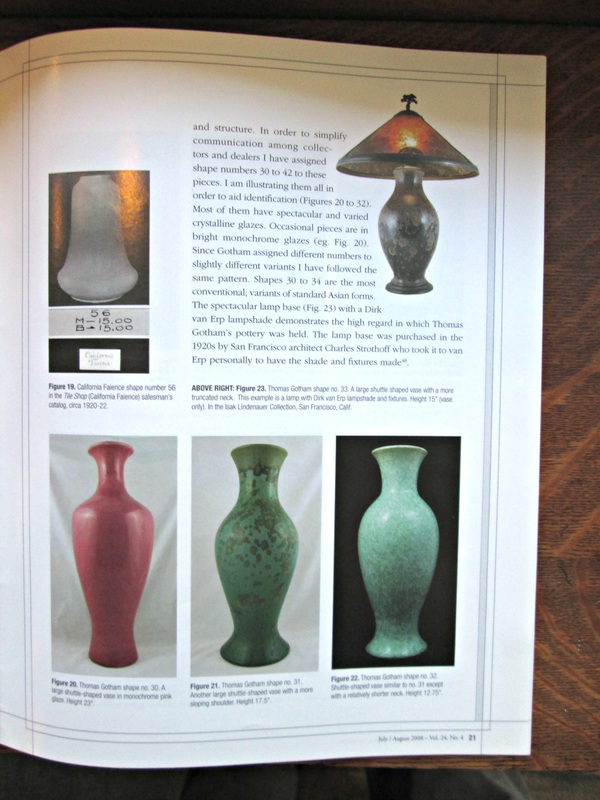

The hammered copper base at the bottom of the lamp is marked with the van Erp hallmark: A windmill and a broken box with the words "Dirk van Erp" and "San Francisco". The bottom of the Thomas Gotham vase has no markings but the cataloged form and this particular lamp are each pictured in Kirby William Brown's extensive article on Thomas Gotham which is the definitive work to date on the life and work of the ceramicist. Often Gotham did not sign his pieces. Sometimes they are initialed. Other times they are merely test numbered. Entitled: Thomas Gotham and West Coast Porcelain; a Mystery Solved. the article appeared in the Journal of the American Art Pottery Association in the July August 2008 issue. Volume 24 number 4. There is a lot to be learned from it. I suggest that anyone interested in Gotham's work back order an issue if there are any issues left. The information is invaluable and the research is extensive. (1)

Strothoff: A brief biography and a recounting of his many, varied architectural accomplishments

Charles F. Strothoff, the architect most well known for two large San Francisco urban neighborhood developments, Westwood Park and Westwood Highlands, was born in 1891 or 1892 in San Francisco. (Established public records give conflicting dates.) "He received his training at the Wilmerding School of Industrial Arts,a building-trades school established by a wealthy San Francisco merchant and administered by the regents of the University of California. The school had been created "to teach boys trades, fitting them to make their living with little study and plenty of work. When the school opened in 1900, it offered training in carpentry, bricklaying, plumbing, architectural ironwork, clay modeling and artificial stonework, wood carving, cabinetmaking, and architectural drawing. Strothoff"..."developed his skills through a combination of vocational education and apprenticeship experiences.

For at least one year, 1912-13, Strothoff served as a draftsman in the office of architect Albert Farr. Farr had established his practice in San Francisco in the early 1900s; at the time Strothoff was working for him, the house that he had designed for Jack London, Wolf House, was under construction in nearby Sonoma County. Farr specialized in domestic architecture with a Tudor or Georgian character, and his designs often reached the baronial in scale. By the 1920's, he enjoyed a well-established reputation as a designer of period houses." (2)

WESTWOOD PARK

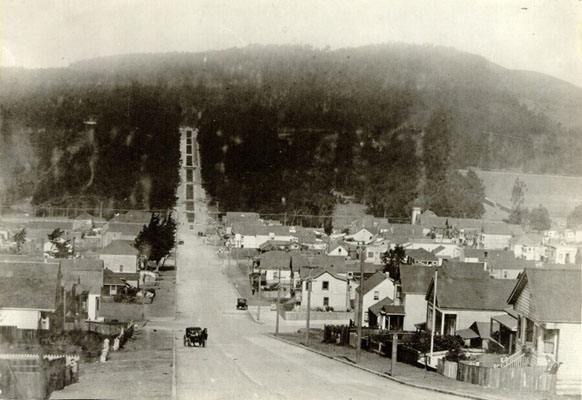

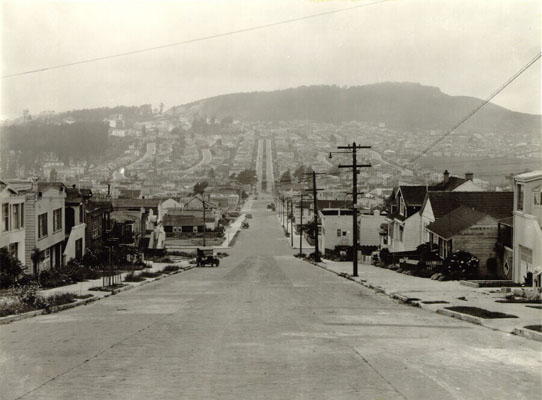

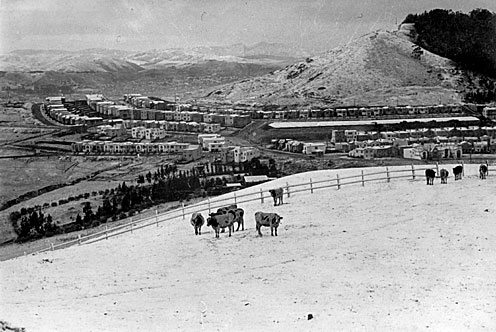

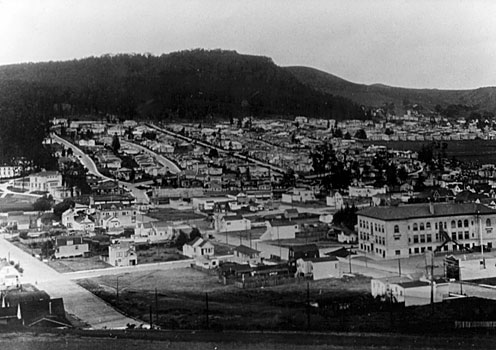

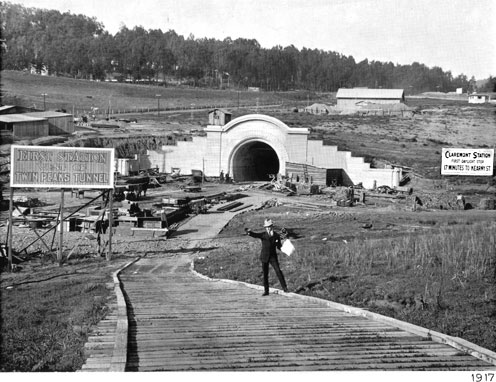

Westwood Park was created in 1917. With the opening of the Twin Peaks tunnel in 1916 areas further away from the now-crowded city's center became accessible. Strothoff was "the architect of nearly 500 of the 650 houses built there between 1918 to 1923. Here you can see example after example of Mission, Craftsman, Prairie, Colonial Revival, English Cottage, and Spanish Revival bungalows all with their own distinct detailing as Strothoff intended. Some of the architectural elements considered standard in an average home include: oak floors with mahogany trim, built-in dining room buffets, wainscoting, French doors with beveled glass,

cove ceilings, tiled fireplaces, sun rooms and multiple windows throughout. On the exterior, tile roofs were de rigueur, as were enclosed entryways and columned porches. And nearly every house had its own yard, front and back." (3)

Charles F. Strothoff, the architect most well known for two large San Francisco urban neighborhood developments, Westwood Park and Westwood Highlands, was born in 1891 or 1892 in San Francisco. (Established public records give conflicting dates.) "He received his training at the Wilmerding School of Industrial Arts,a building-trades school established by a wealthy San Francisco merchant and administered by the regents of the University of California. The school had been created "to teach boys trades, fitting them to make their living with little study and plenty of work. When the school opened in 1900, it offered training in carpentry, bricklaying, plumbing, architectural ironwork, clay modeling and artificial stonework, wood carving, cabinetmaking, and architectural drawing. Strothoff"..."developed his skills through a combination of vocational education and apprenticeship experiences.

For at least one year, 1912-13, Strothoff served as a draftsman in the office of architect Albert Farr. Farr had established his practice in San Francisco in the early 1900s; at the time Strothoff was working for him, the house that he had designed for Jack London, Wolf House, was under construction in nearby Sonoma County. Farr specialized in domestic architecture with a Tudor or Georgian character, and his designs often reached the baronial in scale. By the 1920's, he enjoyed a well-established reputation as a designer of period houses." (2)

WESTWOOD PARK

Westwood Park was created in 1917. With the opening of the Twin Peaks tunnel in 1916 areas further away from the now-crowded city's center became accessible. Strothoff was "the architect of nearly 500 of the 650 houses built there between 1918 to 1923. Here you can see example after example of Mission, Craftsman, Prairie, Colonial Revival, English Cottage, and Spanish Revival bungalows all with their own distinct detailing as Strothoff intended. Some of the architectural elements considered standard in an average home include: oak floors with mahogany trim, built-in dining room buffets, wainscoting, French doors with beveled glass,

cove ceilings, tiled fireplaces, sun rooms and multiple windows throughout. On the exterior, tile roofs were de rigueur, as were enclosed entryways and columned porches. And nearly every house had its own yard, front and back." (3)

(The above photographs and attendant information have all been drawn from Mt. Davidson. org., the neighborhood association's website. I'm grateful for their sharing it with the public.) The following images are from the Street Advisor. They give a colorful idea of the homes today:

Let me interject as an aside at this point, that while Charles Strothoff is certainly not so highly considered as early Arts and Crafts architects like Louis Christian Mullgardt, Ernest Coxhead, Julia Morgan or Bernard Maybeck, he is one of a number of architects who followed these trailblazers, and he was responsible for the democratization of the Arts and Crafts idiom in the Bay Area, particularly in the environs of San Francisco. These internationally recognized architects we have come to know, love, and respect so greatly created masterworks which were commissioned by very wealthy people who could afford to spend incredible amounts of money to build large and magnificent homes. Of course these architect's names became well-known. Yet it is architects who followed, like Strothoff, who made the very Arts and Crafts possibility of bungalows affordable to middle class people and a living reality to many more families in the ensuing years. They put into practice the ethic espoused by people like Gustav Stickley who published plans for Craftsman Homes which could be built by middle class folk all over America, a practice which continued through the twenties and thirties in the Bay Area after the Craftsman movement had all but disappeared from the national consciousness. It is a bit surprising that we do not know their names even though they are not held in reverence like the Greene and Greene's and Frank Lloyd Wrights' are. Certainly, their work is not work at a similar level. It was aimed at building homes for everyday people rather than a rare few from the privileged upper class. As such, one can attribute a different social conscience to their designs and intent which harkens back to the stronger politic aspects of the English Arts and Crafts movement. Americans however, especially wealthy ones, have always held to the belief that bigger is better. Perhaps that is part of the reason these architects have not gained more recognition...

The unique character of Westwood Park prompted the Westwood Park Association to be formed in 1917. It is still active today, "to work with area residents in the last decades to ensure that the enclave of historic bungalows would be preserved by becoming San Francisco's first residential character district.

The area's 3,000 or so residents are, according the the U. S. Census Bureau, a diverse group composed as follows: 55 percent white, 30 percent Asian, 5 percent African American, and the remaining 10 percent of some other race or two or more races. The family of "average means" envisioned when the neighborhood was built has evolved over the last 80 years into one of upper middle class' standing. The median annual household income hovering at $90,000, nearly everyone (85 percent) own his or her home." (3)

There is an important place for homes of this nature and architects of this particular stature alongside the world class heavyweights we have come to know. They deserve recognition and our gratitude for having chosen a path which served many more people. And their vision and work was worthwhile and beautiful.

As enthusiasts of the Arts and Crafts movement, most of us have the tendency to focus on the big names and expensive objects too. Writers like Robert Edwards have argued effectively that the scholars of the period and its exhibitions which focus naturally on the iconic object, but to the exclusion of all else: the lesser known artisans and artists who did not achieve lasting recognition far beyond their time although their art and work is worthy, and the craft work of students in trade and art schools, are missing that most deeply espoused truth of the Arts and Crafts movement: that of living with things around us both of great use and beauty as we know it. Those things are many, more than the famous, the big, and the valuable, and reside in the appreciation of the thousand petaled eye of each and every beholder.

WESTWOOD HIGHLANDS

Westwood Highlands was a second development of Strothoff's design, some 300 homes of his built between 1925 and 1929. He based "housing stock on a modular system of design with careful consideration given to the public facade. There were interchangeable components which could be added or subtracted and configured in different ways: the window, entrance, and garage. Most homes were three module but there were also two and four module allowing for the greatest variation on the street. The private development movement was an instinctive response to the 1906 earthquake and to the increasing population in the city. The movement promoted a lifestyle that was community centric, single family directed, affordable and liveable. The notion of middle-class

residential living was also a large trademark in the promotion of the neighborhood." (4)

Below, examples of the variety of styles of homes built in the area.

Westwood Highlands was a second development of Strothoff's design, some 300 homes of his built between 1925 and 1929. He based "housing stock on a modular system of design with careful consideration given to the public facade. There were interchangeable components which could be added or subtracted and configured in different ways: the window, entrance, and garage. Most homes were three module but there were also two and four module allowing for the greatest variation on the street. The private development movement was an instinctive response to the 1906 earthquake and to the increasing population in the city. The movement promoted a lifestyle that was community centric, single family directed, affordable and liveable. The notion of middle-class

residential living was also a large trademark in the promotion of the neighborhood." (4)

Below, examples of the variety of styles of homes built in the area.

The Sunshine School

"In 1937, built as a Works Progress Administration project (WPA), the Sunshine School

was originally constructed as a school for disabled children. It was designed by architects

Martin, Rist, Charles F. Strothoff, Smith O'Brien, and Albert Schroepfer in a Moorish-

Byzantine inspired style. The school is significant for its architecture, its association with the

WPA, and its association with Franklin Delano Roosevelt's schools for disabled children." (5)

( If you right click on some of the smaller images and then click on "view image", some of these photographs will increase in size, and all will be isolated on the page. In particular, note the extensive tile work under windows and around doors and the stenciling on the wooden beams of the ceiling, an Arts and Crafts detail held over from earlier days...)

"This school was originally built for children with physical disabilities. It later became a continuation high school, and currently houses the SFUSD Cal-SAFE program, the Hilltop School, and various community agencies.

At the time of its construction, it housed 18 classrooms, a courtyard and a therapeutic bathing pool. It was situated near Buena Vista Elementary School, which was also designed for children with various health ailments. The first floor of the building was devoted to crippled children and provided facilities for their education and care. The patio provided a play area in which they could move about freely in their wheelchairs or play various sports activities. The second floor served undernourished children and children with heart problems. The entire building was built from reinforced concrete, is fireproof, and was designed to be earthquake safe.

“The entire building is constructed of reinforced concrete, is fireproof throughout, and is designed to resist both major and minor earthquake disturbances. A considerable use is made of decorative tile which greatly adds to the color and reflection of light. Everything possible has been done to create the most cheerful possible atmosphere in order to encourage the children to forget as far as possible their disabilities. Each dining room is provided with a small stage on the side opposite the doors opening onto the patio. There is a corrective gymnasium on each floor and, in addition to the classrooms on the first floor, there are rooms for manual training, art, music, and domestic science, and a small library…The project was completed in September 1937 at a construction cost of $268,987 and a project cost of $287,713.” –Short and Brown, pp. 185-187.

The interior plan of the school was recommended by a special committee of physicians and educators and was approved by the San Francisco Board of Education.

The building has recently been restored through extensive renovations." (5)

(http://livingnewdeal.berkeley.edu/projects/sunshine-school-san-francisco-ca/)

Other Private Commissions

Charles Strothoff had a number of other private commissions here in the city and the greater Bay Area which included a church, the First Lutheran Church of South San Francisco, which was completed in the early 1950's. It still serves its current congregation well. Strothoff also designed the Bayview Theatre 4935 Third Street, San Francisco. The Bayview opened in the autumn of 1924. It was built at a cost of $50,000. For thirty years it served residents of San Francisco’s Outer Third Street and Bayview Districts, but, like so many others, fell victim to television and closed in 1957, and was then torn down.

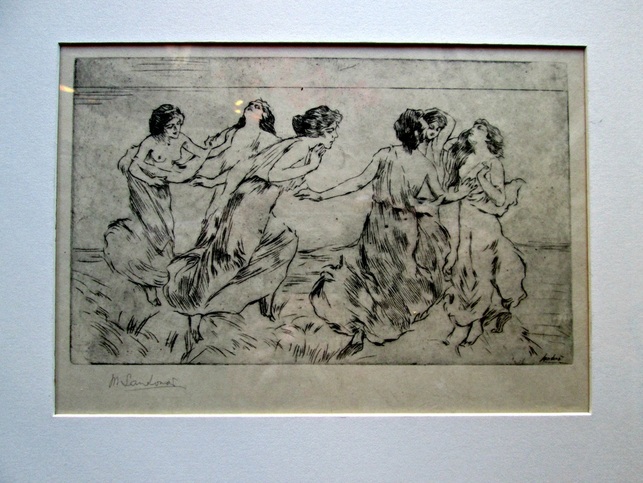

At the beginning of 1920, a residential commission was also taken on by Strothoff for Matteo Sandona, a local artist whose work is well known. This in the midst of the major residential developments he had been spending the majority of his time designing.

The Buena Vista Terrace Studio of Matteo Sandona

Charles Strothoff had a number of other private commissions here in the city and the greater Bay Area which included a church, the First Lutheran Church of South San Francisco, which was completed in the early 1950's. It still serves its current congregation well. Strothoff also designed the Bayview Theatre 4935 Third Street, San Francisco. The Bayview opened in the autumn of 1924. It was built at a cost of $50,000. For thirty years it served residents of San Francisco’s Outer Third Street and Bayview Districts, but, like so many others, fell victim to television and closed in 1957, and was then torn down.

At the beginning of 1920, a residential commission was also taken on by Strothoff for Matteo Sandona, a local artist whose work is well known. This in the midst of the major residential developments he had been spending the majority of his time designing.

The Buena Vista Terrace Studio of Matteo Sandona

Abstract from California Art Research W.P.A. Project 2874, San Francisco Public Library

Matteo Sandona was born in Schio, Italy, in 1883 and was raised in the Alps. As a child he showed talent in drawing and modeling, and his parents encouraged his creative desire. Seeing the potential of his son, Francesco Sandona moved to the United States in 1891 to pave the way for a better life for his family. In Verona, Matteo studied for four years at the Verona Academy and in Paris under Napolean Nami and Moses Bianci. He returned to his family living in Hoboken, New Jersey, and then took further training at the National Academy of Design. In 1901, he and his father settled in San Francisco, California, a climate that was much better for Matteo's father, who suffered from rheumatism. That same year, reacting against the conservatism of the San Francisco Art Association, Sandona co-founded the California Society of Artists with Gottardo Piazzoni, Xavier Martinez, Charles Peter Neilson and William Bull.

Matteo Sandona was born in Schio, Italy, in 1883 and was raised in the Alps. As a child he showed talent in drawing and modeling, and his parents encouraged his creative desire. Seeing the potential of his son, Francesco Sandona moved to the United States in 1891 to pave the way for a better life for his family. In Verona, Matteo studied for four years at the Verona Academy and in Paris under Napolean Nami and Moses Bianci. He returned to his family living in Hoboken, New Jersey, and then took further training at the National Academy of Design. In 1901, he and his father settled in San Francisco, California, a climate that was much better for Matteo's father, who suffered from rheumatism. That same year, reacting against the conservatism of the San Francisco Art Association, Sandona co-founded the California Society of Artists with Gottardo Piazzoni, Xavier Martinez, Charles Peter Neilson and William Bull.

After losing his studio in the 1906 earthquake and fire, Matteo traveled to Europe with his parents, leaving them in Italy while he went to Paris to study. After he spent a year in Paris they returned to California. Sandona himself moved to Santa Barbara in 1911 and married in 1913 to Gertrude Unger.

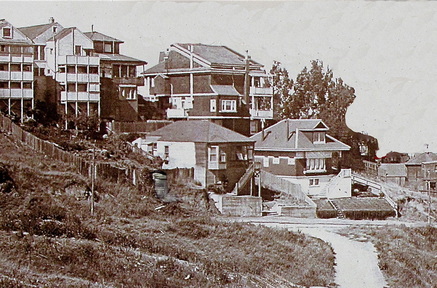

He opened his own studio and exhibited at the Mark Hopkins Institute of Art in 1902 and 1903, and frequently showed at the Bohemian Club in San Francisco. After losing his studio on Clay Street in the 1906 earthquake and fire, he rebuilt the home at 471 Buena Vista East, and he designed and decorated it to resemble an Italian villa. He placed his studio at the front of the structure with a view of the bay. There were four floors behind a Queen Ann façade with a double level studio facing east and south that was his studio. The living quarters were on the lower two floors. In 1922 the home was remodeled again. The Original façade was removed and a studio was built at the front of the building, facing north. The new studio was designed to resemble an Italian villa with Italianate relief accenting the front of the structure. Matteo named his home Villa il Cipresso.

THE BUENA VISTA TERRACE STUDIO ( 471 Buena Vista East)

An article in The Wasp of October 21, 1916, confirms the inherent love of beauty in Sandona' s background, now shared by his wife in their choice of a studio site. "Matteo Sandona has built for himself an attractive studio on Buena Vista Terrace, one of the highest points in the city. Perched up here on the edge of a cliff, with a wooded stretch In front of the studio, the artist, while living in a busy city, is as remote from all disturbing Influence of the city life as he would be in the little city of his birth in Schlo, Italy." In the San Francisco Examiner of May 1, 1921, Robert H. Wilson tells of a few celebrities who have visited Sandona in his studio: "The theory that the world will build its path-way to the door of genius, like all other good theories, is true only in part. The world has so many affairs of its own that it is not exclusively engaged in hunting out genius and it's not a bad idea to have a few sign posts pointing the way. "To find the studio of Matteo Sandona you have to take the 'via circuravallazione' winding about to the far side of Buena Vista Park and there in a sort of hanging garden, you find one of the foremost painters of today. "Mary Garden, Lucien Muratore, Lina Cavalieri, M. Polacco and his wife (Edith Jlason) found their way there, with the result that Sandona has been engaged to do portraits of all of them next year, excepting Edith Mason, and hers is already finished. " In 1920 the Sandonas made extensive changes in their studio-home and the San Francisco Examiner of September 16, 1922, found in it a story which they captioned: "Genius Turns Old House to Ornate Villa": "An Italian villa in the heart of San Francisco, a mountain home on a boulevard, a bit of country over the roofs of Market Street is a recent achievement of Matteo Sandona, San Francisco's famous portrait painter. "Two years ago Sandona had a rambling old house on Buena Vista Avenue that he did not want; nor did Mrs. Sandona like it. Sandona drew a plan of the kind of a house an artist should have. "Today it is the 'Villa il Cipresso,' one of the most unique and attractive studios to be found in any part of the world. "A chapel-like structure has been added to the front of the house, with high, semi-transparent windows and in this large room, with its vaulted ceilings and high lighting, the artist does his work. It constitutes almost a gallery for the exhibition of finished portraits, and the central feature of the room is an immense fireplace. .. .The windows look out over the entire city and across the bay. "The exterior was done by Charles Strothoff, an artist friend. Various bits of Italian relief have been worked into the design and strangers, who wander to that side of Buena Vista Park, stop to wonder whether they are in San Francisco or Firenzo."

An article in The Wasp of October 21, 1916, confirms the inherent love of beauty in Sandona' s background, now shared by his wife in their choice of a studio site. "Matteo Sandona has built for himself an attractive studio on Buena Vista Terrace, one of the highest points in the city. Perched up here on the edge of a cliff, with a wooded stretch In front of the studio, the artist, while living in a busy city, is as remote from all disturbing Influence of the city life as he would be in the little city of his birth in Schlo, Italy." In the San Francisco Examiner of May 1, 1921, Robert H. Wilson tells of a few celebrities who have visited Sandona in his studio: "The theory that the world will build its path-way to the door of genius, like all other good theories, is true only in part. The world has so many affairs of its own that it is not exclusively engaged in hunting out genius and it's not a bad idea to have a few sign posts pointing the way. "To find the studio of Matteo Sandona you have to take the 'via circuravallazione' winding about to the far side of Buena Vista Park and there in a sort of hanging garden, you find one of the foremost painters of today. "Mary Garden, Lucien Muratore, Lina Cavalieri, M. Polacco and his wife (Edith Jlason) found their way there, with the result that Sandona has been engaged to do portraits of all of them next year, excepting Edith Mason, and hers is already finished. " In 1920 the Sandonas made extensive changes in their studio-home and the San Francisco Examiner of September 16, 1922, found in it a story which they captioned: "Genius Turns Old House to Ornate Villa": "An Italian villa in the heart of San Francisco, a mountain home on a boulevard, a bit of country over the roofs of Market Street is a recent achievement of Matteo Sandona, San Francisco's famous portrait painter. "Two years ago Sandona had a rambling old house on Buena Vista Avenue that he did not want; nor did Mrs. Sandona like it. Sandona drew a plan of the kind of a house an artist should have. "Today it is the 'Villa il Cipresso,' one of the most unique and attractive studios to be found in any part of the world. "A chapel-like structure has been added to the front of the house, with high, semi-transparent windows and in this large room, with its vaulted ceilings and high lighting, the artist does his work. It constitutes almost a gallery for the exhibition of finished portraits, and the central feature of the room is an immense fireplace. .. .The windows look out over the entire city and across the bay. "The exterior was done by Charles Strothoff, an artist friend. Various bits of Italian relief have been worked into the design and strangers, who wander to that side of Buena Vista Park, stop to wonder whether they are in San Francisco or Firenzo."

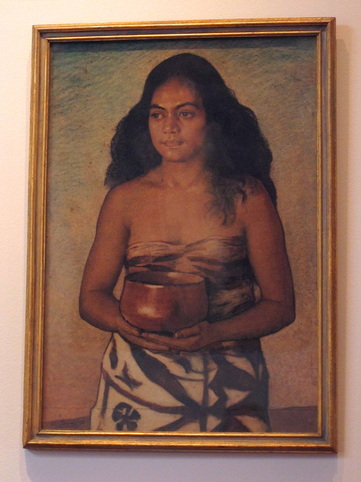

Young Hawaiian girl with an Umeke Poi. (Poi Bowl or calabash.)

He exhibited in many one-man exhibitions between 1919 and 1923. Memberships included the San Francisco Art Association, Carmel Art Association and the Bohemian Club, where he was listed in the 'List of 50'. (6)

Erich Wolf Strattman (7)

55 St. Elmo Way

Among a number of other private residences designed by Strothoff is 55 St.Elmo Way. Built in 1926, this exquisite home was designed by architect Charles Strothoff and built by the Nelson Brothers, who were renowned builders of this era. "In the same family for over 50 years, this remarkable view Spanish Mediterranean estate is an architectural gem and boasts unmatched quality and timeless old world craftsmanship.", say the realtors who sold the property in 2007 for a touch over three million dollars... Wouldn't that surprise Strothoff! It's a beautiful home the front of which is reminiscent of the facade of Sandona's home and studio on Buena Vista Terrace.

Among a number of other private residences designed by Strothoff is 55 St.Elmo Way. Built in 1926, this exquisite home was designed by architect Charles Strothoff and built by the Nelson Brothers, who were renowned builders of this era. "In the same family for over 50 years, this remarkable view Spanish Mediterranean estate is an architectural gem and boasts unmatched quality and timeless old world craftsmanship.", say the realtors who sold the property in 2007 for a touch over three million dollars... Wouldn't that surprise Strothoff! It's a beautiful home the front of which is reminiscent of the facade of Sandona's home and studio on Buena Vista Terrace.

"Strothoff's early career seems to have followed Farr's in its focus on domestic projects, on a

more modest scale. Later, he worked for public institutions, serving as executive director of the

Richmond Housing Authority, across the bay. The nature of Strohoff's employment reflects the

trend in this period toward residential architects working for large developers and state agencies.

He also worked for the San Francisco Recreation and Park Department and for Contra Costa

Junior (now Community) College. Charles Strothoff died in 1963; he had been a member of the

American Institute of Architects since 1944."

Clifford Metz, oral history

by Judith K. Dunning

I end this brief retrospective on Charles Strothoff with gratitude to Judith K. Dunning for allowing me to quote from an oral history taken on Clifford Metz which she gathered for her transcript entitled: A City in Transition: Richmond during World War II: oral history transcript. Metz discusses Richmond during World War II. Ford tank depot. Kaiser Shipyards, new population, changes in racial composition, local entertainment, war housing, Richmond School Department, 1940's, postwar housing, decline of downtown, with an appended interview on family background and early work.

Part of the Berkeley/Richmond Community Oral History Collection from the Regional Oral History Office. The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley.

Metz:

"I had one architect. He was really an inspector. He was really something.

Dunning: What was his name?

Metz: Charles Strothoff, from San Francisco. He was a big six foot six or almost seven feet. He weighed about two hundred pounds. He was a big man. He was an elderly person. He's passed away. He was really a toughie, and I learned a lot about what to look for in construction only through the architects.

I remember one time during inspection of a new elementary school. What the heck was the name? It was right over here in Richmond down off the hill. Anyway, we were building a school there and we went out to look and Charlie said, "All right now, don't forget, red lead around all the drains."

We came back a couple of days later and it was all painted. All done. And that was a big job. Charlie said, "Hey, did you red lead that?"

"Sure. What do you mean? It's in the contract isn't it?"

"Bring me a ladder."

"What do you want? Oh, no, everything's all right Charlie."

He got a ladder and he took a big putty knife and he started scraping all the way along. They hadn't put any red lead in it at all.

Dunning: Red lead?

Metz: That is a preservative for metal, and then you paint over it. They had to take it all off. That's just an incidence that you don't have to put down in here.

Dunning: Well, it obviously still happens today with that big phoney sprinker systems. That's disgrace. [refers to recent incident of contractor installing fake sprinkler systems in California public buildings.]

Metz: That's why you have to have a very good inspector, to catch all those things and know what should be done."(8)

This short oral history gives a strong sense of the character of the man. It serves as a fitting end to this essay.

Isak Lindenauer

Many thanks to Doctor Gray Brechin, Living New Deal, Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley, for allowing me to use images and information gathered regarding the Sunshine School here in San Francisco, to my friend, Kirby Brown, for his permission to use photographs and information from his landmark essay on Thomas Gotham, and to Judith K. Dunning for so graciously allowing me to cite her oral history with Mr. Metz which uniquely brings Charles Strothoff to life once again.

A very special debt of gratitude to Erich Wolf Stratmann who was kind enough to arrange access for me so I could view the studio/home of Matteo Sandona as it is today as well as for sharing personal photographs of the early studio and allowing me to include in this essay images of some of Sandona's most important work.

(1) Kirby William Brown, author of the article on Thomas Gotham. Thomas Gotham and West Coast Porcelain; a Mystery Solved. The Journal of the American Art Pottery Association in the July August 2008 issue. Volume 24 number 4.

(2) Entreprenurial Vernacular: Developer's subdivisions in the 1920's Carolyn S. Loeb

Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London www.press.jhu.edu

(3) San Francisco Street Advisor

(4) Wikipedia, Westwood Highlands

(5) Gray Brechin, Living New Deal, Department of Geography, 505 McCone Hall, University of California, Berkeley 94720-4740

(6) Abstract from California Art Research W.P.A. Project 2874. O.P. 65-5-.363g Volume XIII San Francisco Public Library.

(7) Erich Wolf Stratmann.

(8) Judith K. Dunning, Interviewer, A City in Transition: Richmond during World War II, oral history transcript; Clifford Metz Creator/Contributor. The Bancroft Library,The Regional Oral History Office, 486 Library, University of California, Berkeley, California, 94720

Gratitude also for much information gathered from the websites connected with Westwood Park and Westwood Highlands, The Richmond Public Library, and The San Francisco Public Library.

And lastly, a big "Thank You", to the Strothoff relative who sold me the lamp so many years ago which started my appreciation for Strothoff's life and work in architecture. I hope this brief retrospective of his life and career brings you and your family some measure of pride and pleasure...

Copyright © 2014-2021 Isak Lindenauer