Essay Number Four: February 1, 2014

A Most Unique Dirk van Erp Lamp

Many years ago I had a conversation with one of the most important and influential dealers of the American Arts and Crafts. We were discussing the foibles of the trade. At one point he asked me if I would rather do business or be right. I answered, " I would rather do business and be right..." That's how I felt and still feel. But I never thought I could be right all the time, only try to be. And when over the years there have been times when I was wrong, I haven't had a problem admitting it. We're all human and can only do the best that we can do...

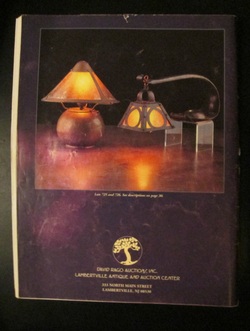

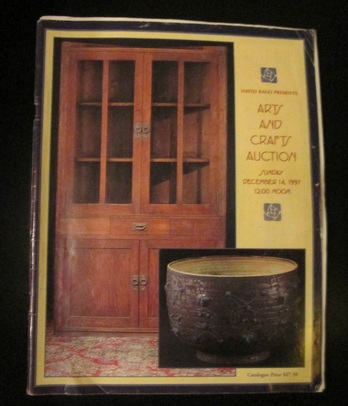

Back cover of David's auction featuring the cobra lamp. (#1)

Back cover of David's auction featuring the cobra lamp. (#1)

The subject of this article is a lamp. My past judgment about it was one of those times when I was wrong. It is the same lamp I saw some sixteen years ago when I arrived to preview a David Rago auction in New York City. It was featured on the back cover of the auction catalog. (#1)

I was there hoping to win the cover lot (#2) and a number of other objects to bring back to my shop in California. When I arrived, to my surprise, I saw the lamp and knew I would have to take a closer look at it as well-not the sort of object you see every day...

I was there hoping to win the cover lot (#2) and a number of other objects to bring back to my shop in California. When I arrived, to my surprise, I saw the lamp and knew I would have to take a closer look at it as well-not the sort of object you see every day...

Cover lot of David's auction featuring the Gustav Stickley corner cabinet. (#2)

Cover lot of David's auction featuring the Gustav Stickley corner cabinet. (#2)

I know a bit about San Francisco copper work from the Arts and Crafts period and a bit more about the work which was crafted by the van Erp studio in particular. I have loved and collected the studio's work since the early 1970's, had the good fortune to know William van Erp and had him do work for me in the last years of the workshop's production. I spent many hours sitting in the workshop next to William and Larry Roberts, the last worker other than William to work there, watching them work, asking them both questions about history and process, and furiously taking down oral histories as they answered me.

In the process of collecting and selling work of this period and tracing backward through found objects and hallmarks, I rediscovered the foreman of the studio, August Tiesselinck, and helped to put together two seminal exhibitions in 1989: the show of van Erp's work at the Craft and Folk Art Museum curated by Dorothy Lamoureaux (#3) and an exhibition in my own shop featuring for the first time in seventy years the work of August Tiesselinck, along with the work of Harry Dixon, Fred Brosi, Hans Jauchens and others from the Bay Area who worked in silver and copper (#4). At the request of its director in 1991, I then organized a major exhibition for the Sonoma County Museum to help them promote the work of Harry Dixon (#5), as his widow, Florence Dixon, intended to leave their work and papers to the museum as its repository. John Lofgren, the Director, had brought Florence to my shop to see my exhibition and both of them had liked very much what I had done. Two years later, John called and asked me if I would be willing to do for them and Harry's work what I had done for August's work; and of course, I was thrilled and said yes.

This little overview, a synopsis of my personal history with Art Copper in California, is given in an attempt to provide some context behind the request for my "expert" opinion in regard to the authenticity of the particular lamp at David Rago's auction and my response to that request, both then and to that recently repeated request only a few weeks ago.

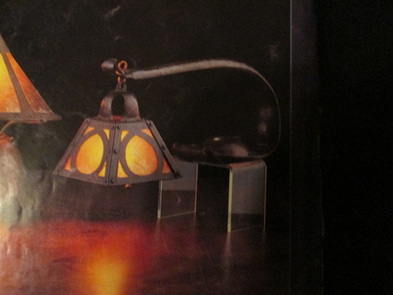

Dirk van Erp cantilevered lamp. Rago auction, 1997. (#6)

Dirk van Erp cantilevered lamp. Rago auction, 1997. (#6)

When I first saw this lamp, I was struck by some major differences in it compared to the other few known examples of this form. Most noticeable was the fact that the connection between the base and the shade had obviously been altered ( #6). And the shade was unlike anything else I had seen before.

In the five to ten years prior there had been a flood of reproductions on the marketplace, good, bad, and otherwise as modern crafters had begun to create contemporary versions of antique lamps so they might capitalize on the high prices the originals had been commanding. The two circumstances together gave me pause. This lamp was being offered at a time when lamps of all kinds were appearing for sale all over the country. New ones based on old designs, new ones which were strange syntheses of disparate designs; even lamps with old parts married to new ones, and this general sort of mixing of design elements still goes on today. People want to earn a living at their trade the best they can. No disrespect to or fault on their part- there is both a monetary imperative as well as the desire to satisfy potential customers who for one reason or another are unwilling to buy original examples or can't find them, yet still want "the look". So one saw then and still sees all sort of ungodly combinations to my eye-

from huge triple, long lanterned, central domed chandeliers which seem as though they are about to fall, which have little or no grace or balance at all, Tiffany style floor lamp bases mixed with van Erp style shades, floor lamps slightly twisted out of authenticity by additional elements, to newly wrought or ceramic table lamp bases with Batchelder and Stickley Brothers designed and reproduced shades. This may be fine for some, but I was spoiled by my having started to collect this period when there was never a question about whether or not a piece was original. There weren't any reproductions back then. Consequently, right or wrong, I see most of these permutated forms as being Frankensteinian in nature.

from huge triple, long lanterned, central domed chandeliers which seem as though they are about to fall, which have little or no grace or balance at all, Tiffany style floor lamp bases mixed with van Erp style shades, floor lamps slightly twisted out of authenticity by additional elements, to newly wrought or ceramic table lamp bases with Batchelder and Stickley Brothers designed and reproduced shades. This may be fine for some, but I was spoiled by my having started to collect this period when there was never a question about whether or not a piece was original. There weren't any reproductions back then. Consequently, right or wrong, I see most of these permutated forms as being Frankensteinian in nature.

Hanging lantern (#7)

(now being reproduced.)

Hanging lantern (#7)

(now being reproduced.)

During that time, I had a unique, one-of-a-kind lantern in my home pictured in my copyrighted catalog on Tiesselinck's life and work (#7). It was "lifted" without my permission and reproduced by the thousands in a tripled version joined to a central chandelier by an unscrupulous West Coast character until there were way too many of these examples, at airports and restaurants, everywhere it seemed, where once there had been only one. As far as I am concerned, this fellow's company makes the shoddiest reproductions of van Erp lamps on the market place today and yet he has made more money selling them than all the other contemporary shops put together.

Most all of the major contemporary crafters have profited more from their own reproductions than most of the antique dealers have selling the originals. That's just the way it is. And that's okay. Most of the dealers in the originals have been involved in selling them because we highly admire the work and are proud to represent it, not because we are looking "to make a killing" every time a good example comes our way. We're treasure hunters in part, but we are mainly urban archeologists, the worker ants, daily builders of the market place. We commit to the objects for the long haul, represent them and pass them on to their new owners and next incarnation. In the midst of that work, I once had a rare stenciled design of a lamp from my same catalog (#8) copied by laser technology by another contemporary, again without having asked my permission to adapt and reproduce it, and there was also a third modern company that hired Mexican smiths (who have some of the greatest technical skills when it comes to moving and shaping metal-it must be acknowledged) who were directed to reproduce a handled tray from my copyrighted catalog. (#9) I ultimately spoke with the woman who headed the company and asked her to at least attribute the work her workers were reproducing and acknowledge the vintage pieces by giving the products names which identified their heritage. She did, to my satisfaction under the circumstances.

It should be said that while I have experienced directly some unfortunate occurrences regarding the copying and stealing of old designs by crafters looking for inspiration or a quick way to produce new pieces, there are a number of modern artisans who have distinguished themselves in the world of contemporary crafts. They are hard at work, making beautiful objects joyously, earning an honest living using their learned skills, their hands, and their hearts to keep a many-thousands-of-years-old tradition alive and thriving. That is no small feat. I had thought to try my hand at metal arts a number of years ago too. Inspired by the San Francisco pantheon of artists in metal, having bought and sold Arts and Crafts objects for a long time, I had first taken a class during the summer in pottery at the wheel. I spent a whole summer, my hands in clay, trying to pull a wall-without ever succeeding. Never completed one piece. I had thought "I love Grueby, Newcomb, Rookwood. I'll sit down and make some modern examples that will be of my own creation that will be wonderful because I know so much about pottery already." Fat chance. I left deflated, miserable, angry at myself, and confused. Why couldn't I do what I had fully expected to excel at? Why indeed! Because it involves a lot more than desire and experience handling antique objects of beauty and virtue. It requires patience and practice, discipline and talent, innate or acquired and practice, and time....and a good teacher or teachers. And finally, more practice! It takes years to learn to make a thing well unless one is blessed with that incredibly rare gift of talent and driving inspiration both. I learned that, that summer in Ruby's studio. The great crafters apprentice for years and years.

I thought after failing so miserably at pottery, I might have better luck working with copper. And thus began a seven year attempt at raising and forming objects in copper. I went to City College which has a great program and was fortunate to encounter a wonderful Zen teacher named Roger Baird. He let me, along with another fellow interested in copper work other than making jewelry which the rest of the class was focused on, try our hands at the art. We even came in on off days because our pounding ceaselessly for hours at a time was making most of the younger students crazy. But he loved our drive and our unstoppable curiosity.

I was soon hooked and enrapt. Someone would come in and say "Aren't you going to break for lunch? You have been hammering for five hours." I had no idea that much time had passed. I had been somewhere else, in the world of craft heaven. I learned very quickly how difficult it was to cut a straight line, to make a clean seam of solder, the extreme patience as well as the excitement, a birthing of sort, which was involved in the metamorphic process of taking a flat sheet of copper, turning it into a cylinder and then, by a series of successive hammerings which open up the metal from the inside into the beginning of an elementary form, followed by torching the intermediate form red hot. That's required because with each strike of the hammer, besides being moved, the metal becomes harder (tempered). It's only by torching it (annealing) that the metal is re-softened so it is once again pliable and can be hammered further after putting it in a pickle to clean it.(a chemical solution which removes the oxides and ash from its surface) How impossibly difficult it was to develop hand/eye co-ordination so that the hammer struck the metal exactly where you wanted it to hit. Then to hit with the same intensity, the same direction, the same rhythm, so that each strike added a planished mark that was as regular and as specifically registered as the one which had preceded it. Oh, how I soon saw that the metal "told" everything to anyone who then looked at your work. Every moment of inattentive motion, every millisecond of disregard was forever reflected in the success, or more-likely-than-not in the failure or comparatively poor nature of one's effort.

Does this attempt at explaining small parts of the very involved process involved in crafting anything in copper make you start to realize a bit more how very artful one's work must be to produce something as wonderful and grand as a Dirk van Erp lamp? I hope so. Just understanding the labyrinths of process is hard enough. Sometimes you would get to a certain point in making a shade and you would realize that you had not thought out the steps clearly enough. What you needed to do next with soldering on the clips for the mica panels of the shade had been precluded by the step you had just completed. Soldering would soften the metal out of form and you couldn't temper the metal once again by striking it without the clips indenting the battens at points and ruining their perfect, flat linearity of which you had been so proud moments before... Or you would suddenly find yourself in another "pickle", which wasn't the chemical solution but rather the word which described the nature of your current physical dilemma! The whole process demanded knowledge and forethought. So after a number of years spent learning, I gained a bit of experience in the love of working with copper, and also a very healthy respect for the artists at the turn of the last century who had far exceeded my feeble venture into the art of craft. That awareness still stands me in good stead.

So at the time of David's auction and for at least five to ten years before, floods of pieces of new/old furniture, new/old pottery, new/old painting were overwhelming the antique market as contemporary craftsmen continued the rush to enter, rise, and succeed in the burgeoning new market of contemporary Arts and Crafts. The intense activity in the lighting marketplace had been occurring in other markets in similar fashion. Personally, I have no problem with that. All artists and crafts people are influenced by those whose work has preceded them. Good or bad, we all learn from one another in life, if not through our own experience directly.

I find that I like best those contemporary crafters whose work clearly shows an indebtedness to older designs yet has an overall feeling of difference and freedom from having copied exactly too many elements of the old or of the piece entire. That is not easy to accomplish when the imperative for some is mostly economic and fine craft is usually labor intensive and often costly, or for others who have no sense of individual inspiration or creative energy directed toward developing designs of their own. And it is made all the more difficult by the fact that the impetus comes from requests for pieces from a period of design in American history which had some of the greatest crafters the American Decorative Arts has ever known. Hard to improve on perfection...

It was a different world one was looking at and the challenges to know the real, or original, from the reproduction or married examples were sometimes not so easy to discern, especially if one were a new, inexperienced collector with good or grand intentions to gather, whether for one's own comfort or to make an impression while decorating a new home in the old style...

I thought after failing so miserably at pottery, I might have better luck working with copper. And thus began a seven year attempt at raising and forming objects in copper. I went to City College which has a great program and was fortunate to encounter a wonderful Zen teacher named Roger Baird. He let me, along with another fellow interested in copper work other than making jewelry which the rest of the class was focused on, try our hands at the art. We even came in on off days because our pounding ceaselessly for hours at a time was making most of the younger students crazy. But he loved our drive and our unstoppable curiosity.

I was soon hooked and enrapt. Someone would come in and say "Aren't you going to break for lunch? You have been hammering for five hours." I had no idea that much time had passed. I had been somewhere else, in the world of craft heaven. I learned very quickly how difficult it was to cut a straight line, to make a clean seam of solder, the extreme patience as well as the excitement, a birthing of sort, which was involved in the metamorphic process of taking a flat sheet of copper, turning it into a cylinder and then, by a series of successive hammerings which open up the metal from the inside into the beginning of an elementary form, followed by torching the intermediate form red hot. That's required because with each strike of the hammer, besides being moved, the metal becomes harder (tempered). It's only by torching it (annealing) that the metal is re-softened so it is once again pliable and can be hammered further after putting it in a pickle to clean it.(a chemical solution which removes the oxides and ash from its surface) How impossibly difficult it was to develop hand/eye co-ordination so that the hammer struck the metal exactly where you wanted it to hit. Then to hit with the same intensity, the same direction, the same rhythm, so that each strike added a planished mark that was as regular and as specifically registered as the one which had preceded it. Oh, how I soon saw that the metal "told" everything to anyone who then looked at your work. Every moment of inattentive motion, every millisecond of disregard was forever reflected in the success, or more-likely-than-not in the failure or comparatively poor nature of one's effort.

Does this attempt at explaining small parts of the very involved process involved in crafting anything in copper make you start to realize a bit more how very artful one's work must be to produce something as wonderful and grand as a Dirk van Erp lamp? I hope so. Just understanding the labyrinths of process is hard enough. Sometimes you would get to a certain point in making a shade and you would realize that you had not thought out the steps clearly enough. What you needed to do next with soldering on the clips for the mica panels of the shade had been precluded by the step you had just completed. Soldering would soften the metal out of form and you couldn't temper the metal once again by striking it without the clips indenting the battens at points and ruining their perfect, flat linearity of which you had been so proud moments before... Or you would suddenly find yourself in another "pickle", which wasn't the chemical solution but rather the word which described the nature of your current physical dilemma! The whole process demanded knowledge and forethought. So after a number of years spent learning, I gained a bit of experience in the love of working with copper, and also a very healthy respect for the artists at the turn of the last century who had far exceeded my feeble venture into the art of craft. That awareness still stands me in good stead.

So at the time of David's auction and for at least five to ten years before, floods of pieces of new/old furniture, new/old pottery, new/old painting were overwhelming the antique market as contemporary craftsmen continued the rush to enter, rise, and succeed in the burgeoning new market of contemporary Arts and Crafts. The intense activity in the lighting marketplace had been occurring in other markets in similar fashion. Personally, I have no problem with that. All artists and crafts people are influenced by those whose work has preceded them. Good or bad, we all learn from one another in life, if not through our own experience directly.

I find that I like best those contemporary crafters whose work clearly shows an indebtedness to older designs yet has an overall feeling of difference and freedom from having copied exactly too many elements of the old or of the piece entire. That is not easy to accomplish when the imperative for some is mostly economic and fine craft is usually labor intensive and often costly, or for others who have no sense of individual inspiration or creative energy directed toward developing designs of their own. And it is made all the more difficult by the fact that the impetus comes from requests for pieces from a period of design in American history which had some of the greatest crafters the American Decorative Arts has ever known. Hard to improve on perfection...

It was a different world one was looking at and the challenges to know the real, or original, from the reproduction or married examples were sometimes not so easy to discern, especially if one were a new, inexperienced collector with good or grand intentions to gather, whether for one's own comfort or to make an impression while decorating a new home in the old style...

Gustav Stickley corner cabinet and

another version of the van Erp

cantilevered lamp. (#10)

Gustav Stickley corner cabinet and

another version of the van Erp

cantilevered lamp. (#10)

On first view of the lamp in question, I had my doubts as to the authenticity of the shade. I never doubted that the base was an original van Erp. If I were right about the shade, then my concern for David was that he not sell a lamp which had been married and represent it as being an original; especially a rare form, lest it come back to haunt him after the sale. Because there was little time to do much more than tell him I thought he would be better off being safe than sorry, I stated that the lamp was troubling to me and recommended he withdraw it from the sale. I have been in business for forty-one years. I have never told an auction house before that, based on my considered opinion, they should pull an object. I never have since. It was a serious decision for me to go ahead

with that recommendation. I had little time to examine the lamp and little time in which to make as considered a judgment as was possible. I was at the preview the day before the auction on business of my own. There were other objects there I needed to examine carefully before bidding on them in the hope of then bringing them back to California to offer in my shop. As it turned out, I was lucky enough to win the cover lot (#10), the major piece I had flown out East to bid on, and a dozen or so other things I had wanted too. But in the process of looking at the field of objects being offered for sale, I saw the cobra lamp and looked it over as best I could. The constraints of time being what they were, perhaps I would have been better not saying anything at all. That is moot at this point. Instead, back then, I dared.

with that recommendation. I had little time to examine the lamp and little time in which to make as considered a judgment as was possible. I was at the preview the day before the auction on business of my own. There were other objects there I needed to examine carefully before bidding on them in the hope of then bringing them back to California to offer in my shop. As it turned out, I was lucky enough to win the cover lot (#10), the major piece I had flown out East to bid on, and a dozen or so other things I had wanted too. But in the process of looking at the field of objects being offered for sale, I saw the cobra lamp and looked it over as best I could. The constraints of time being what they were, perhaps I would have been better not saying anything at all. That is moot at this point. Instead, back then, I dared.

The cogent concerns at that time were: The tons of reproductions of all kinds on the market in the recent years before the sale, the fact that the lamp had obviously been altered already to some degree however slight that may have been, that the shade was unlike any other example I had ever seen, that there were a few other condition issues with it: a side of the shade was bent out of its original position (#11), there were separations in the soldering at one point in the upper portion of the shade (#12), the hood had a crimp (#13) and the front of the base was flattened somewhat (#14 & #15) and that too raised concerns, and finally the puzzling fact that this shade differed substantially from other examples of all the other van Erp cantilevered lamps I knew. I had never seen a trapezoidal shade like this one, nor had I ever seen a large circular copper cut-out braced by four struts in the middle of a shade as its central design element before. Lastly, and importantly, I had no idea of the lamp's back story. How had this lamp come to be owned by the consignor? Where had it originated and what might have been done to it once the original loop from where the shade had hung had disappeared?

(All of the following views of the lamp, courtesy of the lamp's consignor.)

(All of the following views of the lamp, courtesy of the lamp's consignor.)

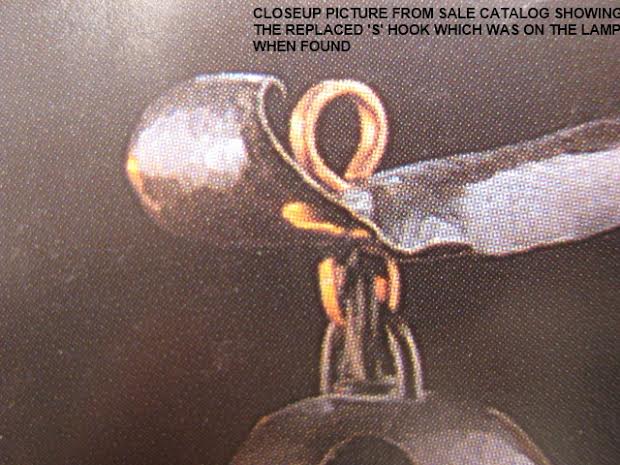

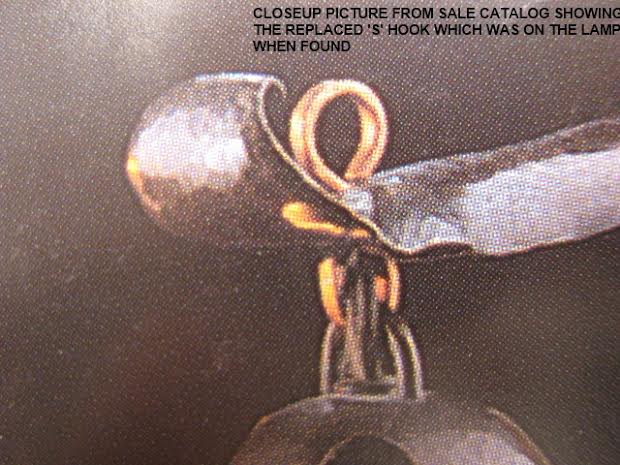

Now to be more specific about the shade, let me say this about these lamps which have been variously called: a cobra lamp, a piano lamp, or a desk lamp. These lamps are exceedingly rare forms. In forty plus years, I know of five. This lamp would be the sixth in my experience. That doesn't mean that there are no others; only that these are all which I have encountered in all these years. There may be another, three others, even twenty others. Rarity is mostly indeterminate and also ever-changing. All of the others I know of have conical shades. All have an ovoid shaped base with an arm which extends up and out over the base. Three have had hanging conical shades which hung from a loop atop the shade and have been attached to the armature with a hook (#16), two have had conical shades which attached by a swivel joint attached to the armature above the shade (#17). None have had a trapezoidal formed shade other than the one in question.

close-up of the shade on the cantilevered lamp. (#19)

close-up of the shade on the cantilevered lamp. (#19)

So this shade was the object of my scrutiny and the central focus of my concern. Not only was it a singular example of this sort of shade on a cobra lamp, it was also the only example in van Erp's repertoire which was both this shape and also what I will call highly constructed.(#18) The battens stand out visually. They are separate pieces of copper which have been folded and are punctuated by being riveted three times-at the top, mid-line and bottom of the shade's four outer edges.(#19) This is also completely atypical in regard to van Erp's general designs.

I have always thought of van Erp's lamps as being, by nature, a range of philosophical and meditative forms expressed, even enhanced, through a degree of purity or what appears to be simplicity in their execution. The work is in many ways "seamless". That is not to say that there are no seams in van Erp; of course there are-even literally in the sides of vases and lamp bases. In fact the lap jointed juncture of the folded metal subsequently opened and formed into a variety of shapes is left visible to show in a discrete way that the lamp or vase has been formed by forthright hand work. It is evidence of the high degree of craftsmanship required to open up a simple cylinder and turn it into the subtle, elegant forms for which van Erp's work came to be held in such high regard. It designates at the same time how subordinate that craftsmanship was to the overall effect of unity and sublimity one feels when looking at one of them. The overt presence of the sense of the parts which comprise this shade is in that way antithetical to that sort of intent. One sees this constructionist work in lamps by other crafters but rarely in van Erp. But that is not meant to suggest that there are no rivets in van Erp's work. That is not true either.

There are rivets used throughout his designs. But they are used with explicit intent and almost always sparingly to join parts with a restraint not evident in this shade. Nonetheless they are found exuberantly around the collars and the bases of some of his lamps. There are gourd forms which have rivets which circle, like necklaces, the necks of their bases.(#20) And there are lamps which have rivets around the bottoms of the standards of their bases where they connect to bowl forms to create a lamp. These are so prominently utilized in the crafting of the form that we refer to these lamps as rivet base lamps.(#21)

There are also rivets used decoratively in boxes and letter openers, bookends and picture frames but in almost all of these pieces the rivets are as functional as they are decorative, perhaps even more so. (#22, #23)

The shade top with featured flanged supports. (#24)

The shade top with featured flanged supports. (#24)

In this example of the cantilevered lamp the shade feels altogether more "put together", more constructionist or a composite of parts, rather than a seamless whole. As I have just noted, the four battens which form the outer canted sides of the shade are cut, applied, and also riveted to the top and bottom frames. Add to that the four curvilinear and flanged supports which are riveted to the top of the shade (#24); again a construction and design form which I am hard-pressed to point to in other van Erp pieces. The constructed look is even further emphasized by this conventionalized floriform attachment and a third rivet in the middle of each of the side struts which seems to have no function except to emphasize the "joining" elements. This type of constructed work is more often seen in the copper work of other Arts and Crafts artisans.

Turtleback chandelier by August Tiesselinck. (#25)

Turtleback chandelier by August Tiesselinck. (#25)

There are certainly riveted handles on the sides of flower boats which often exhibit cut-out designs, there are flanged, flattened ends to rods of copper which form handles on coal scuttles, and pitchers, and there are patterned feet which are attached to reed baskets by van Erp and such. I do not recall though any shade by van Erp which has this four sectioned surmount by which it is then hung. In fact hanging shades by van Erp are rare as hen's teeth. Most of them, whether what is commonly referred to these days as an "uplighter" or larger forms like the Tiesselinck turtleback chandelier (#25) hang from a simple loop of one sort or another and a subsequent length of chain.

Dirk van Erp trapezoidal boudoir lamp. (#26)

Dirk van Erp trapezoidal boudoir lamp. (#26)

The shade which most closely resembles the shade on this cantilevered lamp can be seen on a small table lamp I own. It is pictured in the catalog of the Dirk van Erp Studio, companion to the San Francisco Craft and Folk Art exhibition of 1989. It is on page 38, figure 8. I include an image of it here for comparison's sake. (#26) This little lamp, which was purchased directly from the Berkeley home of two professors who taught at the University, a home in which it had been since they purchased it from the van Erp studio, also has a trapezoidal four-sided shade. It sits on four struts which are planished, bent at the base, and riveted to it both as design and construct in equal parts.

Close-up of boudoir lamp by van Erp. (#27)

Close-up of boudoir lamp by van Erp. (#27)

But the shade is what I would call "seamless" by comparison. (#27) The battens are soldered to the shaped and hammered top and the bottom edge is rolled and also soldered to the sides. There is a quiet unity to all the parts. It does not "declare itself" constructed. Instead it suggests something very different. The shade sits as a whole element on these four raised, flat standards which are its "architecture" as it were.

Dirk van Erp flat-top table lamp. (#28)

Dirk van Erp flat-top table lamp. (#28)

All that having been said, there are always anomalies, and I have come to believe this cobra lamp is one of them. It could be argued that the circular cut out in the center of the mica panels of this lamp has references found in the later cut out panels of the van Erp flat-top lamps. (#28) I believe those relate to a gift, a pewter plate August gave to his wife Jean when they first fell in love. August loved plants and flowers. His interest went as far as to be botanical. I have a book he made while still a young man in Holland which has pressed flowers from all over the countryside.They all have their common and botanical names beside them and conventionalized drawings of each as well. I believe he is the person responsible for having introduced Japanese stencils into the van Erp repertoire based on that interest and the fact that when he became foreman of the Lillian Palmer Shop, those stencils also became a part of that studio's repertoire as did hand-painted floral screen shades. Most of the better ones were executed by Tiesselinck himself who was known for specializing in the crafting of the chandeliers and hanging lamps for Miss Palmer's shop.

The pewter plate August made for Jean when he first began to court her. (#29)

The pewter plate August made for Jean when he first began to court her. (#29)

The flat top lamp takes its conventionalized forms from a central medallion of flowers blooming on a vine which is repeated around the border of the plate in rhythmic curves. (#29) His heart is "flowering" with feeling and his designs reflect that emotion in the loveliest way. So it may be said that there are comparisons which can be drawn to support the idiomatic relationship of the use of a cut out circle in the shade of the cantilevered lamp coming up for auction at David's this March.

Close-up of the shade on my lamp. (#30)

Close-up of the shade on my lamp. (#30)

The same can be said for the curved petals of the copper quatra-formed corolla which holds the shade. If one looks at the shade on my example, and thinks transformation and evolving design, that four square corolla could be said to have undergone a significant change.

The essential design element, having been moved downward from atop a trapezoid shade, has now metamorphosed into a petal-form element of the shade itself. (#30) So once again, relationships can be drawn between the distinct and unusual elements of the lamp David is offering and other examples of lamps in the van Erp lexicon.

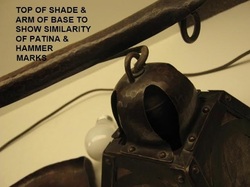

close-up of the hook and loop construction on my lamp. (#31)

close-up of the hook and loop construction on my lamp. (#31)

However much may have happened to the lamp in the years before it came to be in the current owner's possession, Having spoken at length with him about how he came to purchase it, I am now entirely convinced, that the shade is original to the base. Believing that to be the first truth from which to start speaking about the lamp's condition, the ensuing questions then change significantly. No longer is the question of marriage of an old base and a new shade the major consideration. The similarity of the patina along with the now-known back story speak much more to the probability that the shade and base are original and that the connection is what has mostly undergone some changes. So how did that hook get lost? I think it is entirely possible that the lamp may have fallen, been knocked off what it may have been placed upon, or even dropped at one point. That is the most logical way I can explain the crimp in the hood, the dislodging of the small hook in the middle of the hood which was originally held in place by the riveted end of the hook itself ( here, see the top of my cobra lamp for an image of the hook and loop construction from which the shade hangs (#31) and the tiny riveted end which is exposed atop the end of the lamp's arm.

top of the cobra hood with the tiny hook end, slightly flattened to attach it. (#32)

top of the cobra hood with the tiny hook end, slightly flattened to attach it. (#32)

A bend or hit could easily widen the hole enough to dislodge the hook (#32), cause the bent side of the shade and the breaking of a soldered joint at the top of the shade, the crimp in its hood (#33), and maybe also have been responsible for the flattening of the extended edge on the front of the base in the process. Look at the pictures of the lamp and compare it to similar points on the second version I show ( excuse the dust!) and you can see what I mean. The simplest way this might have occurred happens when one pulls the chain to light the bulb. This form is a delicately balanced one. If someone goes to turn on the light who has no knowledge of its unusual nature and weight and the lamp's socket pull chain is pulled without one's first having put a hand on the curved arm or the base to stabilize it, it is entirely possible to pull the shade downward in the process along with the chain causing the lamp to tilt forward and/or fall. Whether I am right or wrong, it seems the simplest explanation for the lamp's current state, explaining how all the small changes could have occurred in one event.

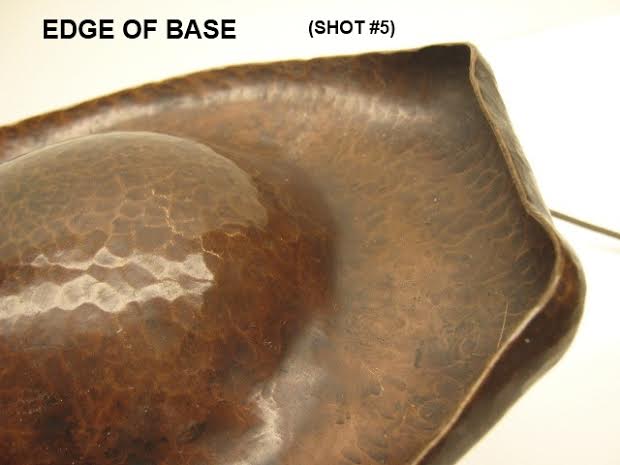

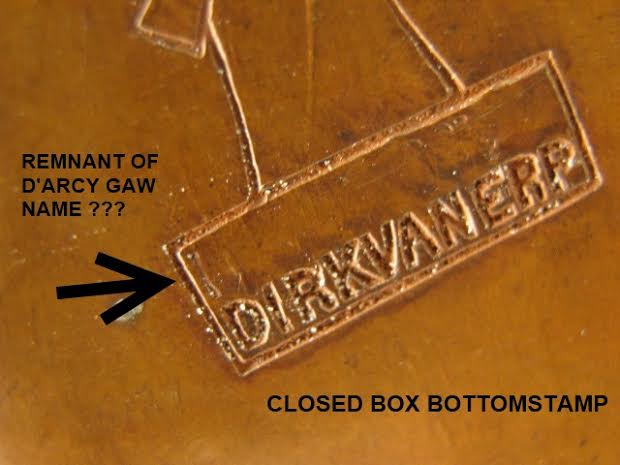

Regardless of these issues which are relatively minor because copper is a forgiving metal and easily restored, the abiding fact is the lamp ((#34) is early based on its mark (#35). While no other shade of this sort has ever been seen publicly to date, it seems probable that when this form of lighting was first attempted the shade may have been constructed differently from ensuing versions.

It may in fact turn out to be the only one of these versions extant. Many designs go through a period of evolution as their forms and functions are considered, created, reconsidered, and refined. Sometimes function demands changes in the design. Sometimes construction techniques are honed as a form is reproduced a number of times. Perhaps the changes occurred as the result of an aesthetic judgment, perhaps considerations of weight and function were more the reasons for the change to conical shades. We may never know. The main challenge with all of these lamps is how to use them without having the shade hit the top of a bookcase, desk, or piano. Perhaps, initially the crafter decided that a smaller shade would make it easier to use this cantilevered form to its best advantage. Perhaps, even though it might have been easier to use, the little shade left something to be desired in other ways. None of these surmisings tells us much, but each does suggest some of the problems crafters face when a piece is unusual and its function demands the incorporation of certain specifics so the form serves its purpose well.

Having had the unusual opportunity sixteen years after the fact to right a wrong I made with the best of intentions, this little appreciation of the van Erp cantilevered lamp which David Rago will be offering for a second time is meant to serve as an apology to both the consignor who has been considerate enough to have already excused me and to David whom I respect immensely. My sole intent at the time was to protect David and the buying public as well as the reputation of the van Erp studio whose work I personally esteem. The same illustrious dealer of the Arts and Crafts who asked me the question I shared at the beginning of this article also said to me recently that he felt he knew his specialty in the field better than anyone else.That notwithstanding, he declared that he still makes mistakes and learns new things constantly as a vital part of the learning process. We're on the same page in that regard. So I'm grateful that fate has allowed me a second chance to correct one of mine from the 1990's. At least the public will be able to bid without restraint this time, and with greater confidence that the lamp is right. And some lucky collector will have the rare opportunity to live with a singular, early example of these rare lamps by what is arguably the most distinguished copper workshop of the American Arts and Crafts movement.

It may in fact turn out to be the only one of these versions extant. Many designs go through a period of evolution as their forms and functions are considered, created, reconsidered, and refined. Sometimes function demands changes in the design. Sometimes construction techniques are honed as a form is reproduced a number of times. Perhaps the changes occurred as the result of an aesthetic judgment, perhaps considerations of weight and function were more the reasons for the change to conical shades. We may never know. The main challenge with all of these lamps is how to use them without having the shade hit the top of a bookcase, desk, or piano. Perhaps, initially the crafter decided that a smaller shade would make it easier to use this cantilevered form to its best advantage. Perhaps, even though it might have been easier to use, the little shade left something to be desired in other ways. None of these surmisings tells us much, but each does suggest some of the problems crafters face when a piece is unusual and its function demands the incorporation of certain specifics so the form serves its purpose well.

Having had the unusual opportunity sixteen years after the fact to right a wrong I made with the best of intentions, this little appreciation of the van Erp cantilevered lamp which David Rago will be offering for a second time is meant to serve as an apology to both the consignor who has been considerate enough to have already excused me and to David whom I respect immensely. My sole intent at the time was to protect David and the buying public as well as the reputation of the van Erp studio whose work I personally esteem. The same illustrious dealer of the Arts and Crafts who asked me the question I shared at the beginning of this article also said to me recently that he felt he knew his specialty in the field better than anyone else.That notwithstanding, he declared that he still makes mistakes and learns new things constantly as a vital part of the learning process. We're on the same page in that regard. So I'm grateful that fate has allowed me a second chance to correct one of mine from the 1990's. At least the public will be able to bid without restraint this time, and with greater confidence that the lamp is right. And some lucky collector will have the rare opportunity to live with a singular, early example of these rare lamps by what is arguably the most distinguished copper workshop of the American Arts and Crafts movement.

Postscript: February 15th. David's catalog is now on line. The side view of the van Erp lamp which I did not see in my not "in hand" re-appraisal makes it fairly clear that the foot of the lamp is original. The form is rounded up intentionally in regard to balance, like a ship's prow.

At least, in my opinion...

Isak Lindenauer

Copyright © 2014-2021, 2020-2025

Isak Lindenauer

At least, in my opinion...

Isak Lindenauer

Copyright © 2014-2021, 2020-2025

Isak Lindenauer